Is China a democratic country?

For many people, the answer to this question is so obvious that even asking it seems funny. But for a large part of the Chinese population, especially schoolchildren, the answer is “yes,” because the most authoritative book they know–their textbook–asserts: “Our country is a country in which the people are the masters of their own house. The people are the masters of the country. The power of the state comes from the people.” (High School Politics (Required) Volume 2, People’s Education Press.)

Such language is ubiquitous. The white paper “Democracy in China” has this to say about China’s current system of “whole-process democracy”: “Whole-process people’s democracy integrates process-oriented democracy and results-oriented democracy, procedural democracy and substantive democracy, direct democracy and indirect democracy, and people’s democracy and the will of the state; it is a full-chain, all-encompassing, and full-coverage democracy, and it is the broadest, truest, and most functional socialist democracy.” (For English readers who also understand Chinese: note how the last sentence in the official English translation in the above hyperlink does not translate the original Chinese word for word and summarizes instead.)

Any Chinese youth who received compulsory education is familiar with this language. A humanities-track student who depends on China’s college entrance examination for upward mobility must not only memorize these correct words, but also elaborate on their logic in the short-answer questions in the politics exams. Students also have to keenly and accurately identify words that seem similar to the party’s discourse but are in fact erroneous. For example: “China is a one-party dictatorship, true or false?” Good students will immediately identify the trap because their politics teacher will have prepared them well by explaining: China is a country with one-party rule and multi-party participation in politics; it is definitely not a one-party dictatorship.

Even a student who studies religiously needs to spend a lot of brain power to understand the concepts in the politics textbook. For example, for why China is not a “one-party dictatorship,” most people can only resort to a simple secular understanding. It’s because “dictatorship” does not sound good, and “dictatorship” is not a good word in any context. However, what is the meaning of “people’s democratic dictatorship” in Article 1 of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China? Why is “people’s democracy” put together with “dictatorship”?

Political concepts such as democracy and dictatorship have become a mystery to many people who went through China’s compulsory education. The basic meaning of democracy has been hollowed out through the short answer questions in the politics exams that need to be churned out in bullet points like ChatGPT. What exactly is democracy, how does a democratic society function, how do citizens in a democracy act? These supposedly simple questions have become difficult ones that most Chinese people never thought of and cannot answer.

But is democracy really so difficult to understand? Is it something that requires a great deal of brain power to grasp accurately? In the modern Chinese language, is there a simple statement of the meaning of democracy? Is there a language like the Declaration of Independence of the U.S., whose exposition of basic human rights is open to all and appeals to all? The answer is yes.

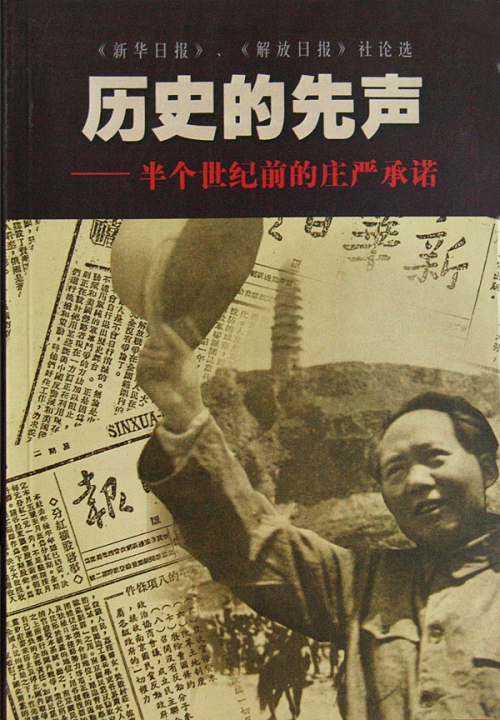

A collection of such language was officially published and briefly circulated freely in China more than twenty years ago. The book is called The Herald of History: The Solemn Promise of Half a Century Ago. This book contains excerpts of pre-1949 discourses on political concepts and universal values such as democracy, freedom, human rights. The authors? None other than Chinese Communist Party leaders, including Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Liu Shaoqi, along with editorials by Chinese Communist Party newspapers, such as Xinhua Daily and Liberation Daily. Organized into a book by the writer and commentator Xiao Shu, it was published by Shantou University Press in 1999.

The publisher wrote in the foreword:

“Re-reading the words of 50 years ago makes us see that the invectives and slanders against our party and our country from outside the country today have no historical basis. Long before western dignitaries took to the stage of history, our party’s revolutionaries and theorists were already outstanding fighters for democracy and human rights. They made their choice between democracy and dictatorship, freedom and autocracy, human rights and repression, and fought to the death for these values.”

The words in The Herald of History are different from the language of today’s Chinese authorities, whose extensive use of parallel phrasing, rhythmic repetitions, along with a series of technical terms, such as “full-chain, all-encompassing, and full-coverage,” make readers confused yet in awe. The language used by the Chinese Communist Party before 1949 was simple, direct, easy to understand, and humorous, to quote a few of the book’s many examples):

“Every American soldier in China should be a living advertisement for democracy. He should talk about democracy to every Chinese person he meets. American officials should talk about democracy to Chinese officials. In short, the Chinese respect the American ideal of democracy.” (Mao Zedong with visiting American officials in Yan’an, 1944.)

“Some people say: Although China needs democracy, democracy in China is somewhat special in that it does not give freedom to the people. The absurdity of such a statement is the same as saying that the solar calendar applies only to foreign countries and that the Chinese can only use the lunar calendar.” (1944 Xinhua Daily editorial, “Democracy is Science.”)

“Mr. Huang [Yanpei] said it well: democracy is not a problem, for there must be democracy, but what we are afraid of is false democracy.” (Short commentary in Xinhua Daily, 1944.)

“The key to the present implementation of democratic politics lies in ending one-party rule.” (Editorial in Liberation Daily, 1941.)

“So there are two kinds of newspapers. One kind is the newspaper of the people, which offers the people the true news, inspires them to think democratically, and tells them to smarten up. The other is the newspaper of the new authoritarians, which tells the people rumors, closes their minds, and makes them stupid.” (Article commemorating the eighth anniversary of the founding of Xinhua Daily, January 11, 1946.)

Today it’s still possible to find these words scattered and separate–in Mao’s selected works, for example, or on online newspaper databases. But taken together the words were too much and the book was banned two months after being published.

The very fact that The Herald of History has been censored is absurd. Of course, at a time when “Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!” can be censored, the Chinese people are probably not so easily surprised. Censorship’s goal is to suppress dissent and eliminate heresy, confining thought by restricting language. How can a regime’s censorship deem its dear leaders as dissidents and regard words from its own mouthpiece as heresy?

One of the characteristics of modern totalitarianism is the inconsistency between its words and deeds, but it gives people the illusion that what it says is what it does, and what it does is what it says, and that both its words and deeds are correct.

To create such an illusion, language must first be rendered meaningless. When the Chinese Communist Party competed for power, it talked about “democracy” as it did in The Herald of History. This was the democracy close to the American ideal as described by Mao Zedong, the democracy with “one person, one vote,” and democracy that is meaningful. However, after coming to power, the Chinese Communist Party’s “democracy” became “people’s democracy” and “whole process democracy.” The party even proclaims China as the largest democratic country and even more democratic than other major democracies.

Democracy in foreign countries is portrayed on television as people queuing up and taking turns to enter a voting booth, while Chinese people only line up just to check out at the supermarket, or to go through various security checks, or to have their noses and throats poked for COVID-19 tests. Not once did the Chinese people ever come out in the hundreds of millions and cast their votes to elect a national leader.

When there is no one-person-one-vote election, no system of power transfer based on such elections, and not even any reliable rules of power succession within the party, how can China speak of democracy?

This destruction of the meaning of “democracy” is similar to Orwell’s 1984, when the thoughts in “Oldspeak” were replaced by the thoughtless orthodoxy of “Newspeak.” When the word “democracy” loses its meaning, the struggle for democracy itself will be missing its foundation. This also means that the Chinese people’s pursuit of democracy, human rights, freedom, and other universal values is not starting from zero. They must seek to fight from negative to zero. This is because in the state of starting from zero, language has not yet lost its meaning, values have not yet been distorted, and “Newspeak” has not yet twisted people’s perception of reality.

What The Herald of History does is to gather the once vivid and undisturbed language of democracy, freedom, human rights. Because its words come from the founders of the Communist Party, it strongly challenges the current political discourse monopolized by power.

The Chinese authorities’ fear of The Herald of History is precisely Newspeak’s fear of Oldspeak, the fear of empty words for lively words. Now Chinese authorities are continuing to perfect their Newspeak with new words and new concepts, using grandiose, abstract, complex, and semantically ambiguous rhetoric to hollow out language and reality, monopolize the narrative, and abolish thought, minimizing the living space for language that is lively, meaningful, and thoughtful.

Nowadays, if we want to pursue the democracy, freedom, and human rights that the Chinese Communist Party promised the Chinese people before 1949, we need to recognize the current rhetoric monopolized by power, and pay attention to what kind of reality the officialdom is trying to create and normalize with language.

We also need to rediscover, use and protect living words such as those included in The Herald of History, to construct a meaningful language that is not monopolized by power, and to remember what the words in The Herald of History tell us–the meanings of democracy, freedom, and human rights.