Explore the collection

Showing 152 items in the collection

152 items

Book

Long Memories after the Hijacking -- Chronicle of Ten Years of Turmoil

The author of this book, Mu Xin, was an early member of the CPC and served as chief editor of "Guangming Daily" in the 1950s. At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, he was a member of the Central Committee's Cultural Revolutionary Group. In 1967, he was defeated and imprisoned in the Imperial Prison (Qincheng Prison). This book was published in Hong Kong in 1997. Because of the author's status, this book is helpful for understanding high-level circumstances during the pre-Cultural Revolution and early Cultural Revolution period.

Book

Mao in Power (1949-1976)

The author of this book, Shan Shaojie, is a scholar from mainland China. For several years, he wrote this book from an independent position. Former political secretary of Mao Zedong, Li Rui, and Princeton University professor, Yu Yingshi, wrote the foreword for this book. In addition to a systematic account of the Maoist era, Shan Shaojie's book "Mao in Power" emphasizes that almost all members of the Communist Party's highest decision-making echelons, with the exception of Mao Zedong, made efforts, in varying degrees and successively, to stop Mao's insanity. Moreover, they took turns to resist and ultimately to leave Mao alone, but did not really stop Mao's madness. This book was published by Linking Publishing in 2001 and has been reprinted several times.

Book

Mao Zedong and the Cultural Revolution: an interpretation of political psychology and cultural genes

This book systematically explores the mental world of Mao Zedong, and his followers (including Lin Biao, Jiang Qing, Zhou Enlai, Kang Sheng, and Zhang Chunqiao). According to the author, it involves lust, political fantasies, and other pathologies. The book analyzes how these subconscious thoughts underlay the history of the Cultural Revolution.

Book

Mao: The Unknown Story

This book presents the dramatic life of Mao Zedong, revealing a wealth of unheard-of facts: why Mao joined the Communist Party, how he came to sit at the top of the Chinese Communist Party, and how he seized China step by step. Writers Jung Chang and her husband Jon Halliday took ten years to complete this book, interviewing hundreds of Mao's relatives and friends, Chinese and foreign informants and witnesses who worked and interacted with Mao as well as dignitaries from various countries.

Purchase link:https://www.amazon.com/Mao-Story-Jung-Chang/dp/0679746323.

Book

Memo of the Educated Youth: Production and Construction Corps of the "Down to the Countryside" Movement

During the Cultural Revolution, 14.03 million urban junior and senior high school students said goodbye to their parents and families and left the cities to receive "re-education" in the "wide world." 10.48 million young intellectuals who had been sent to the army or returned to their hometowns were resettled in rural communities and squads. 1.26 million were placed in the newly-formed youth collectives and teams, while another 2.29 million were accepted by state-run farms and production and construction corps. The production and construction corps became the most concentrated place for intellectual youths, and had an undeniably important position in the whole movement of educated youths going to the countryside. This book describes the rise and fall of the production and construction corps and the fate of the educated youths who went to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution.

Film and Video

Memory of Lin Zhao

Independent director Tiger Temple began shooting this film in 2010 and completed it in 2012, with subsequent revisions. The film features interviews with Lin Zhao's former lover Gan Cui as well as interviews with several independent scholars such as Qian Liqun and Cui Weiping. It is a powerful addition to Lin Zhao's memory. This film was selected as one of the top 20 finalists in the 2012 Sunshine Chinese Documentary Awards.

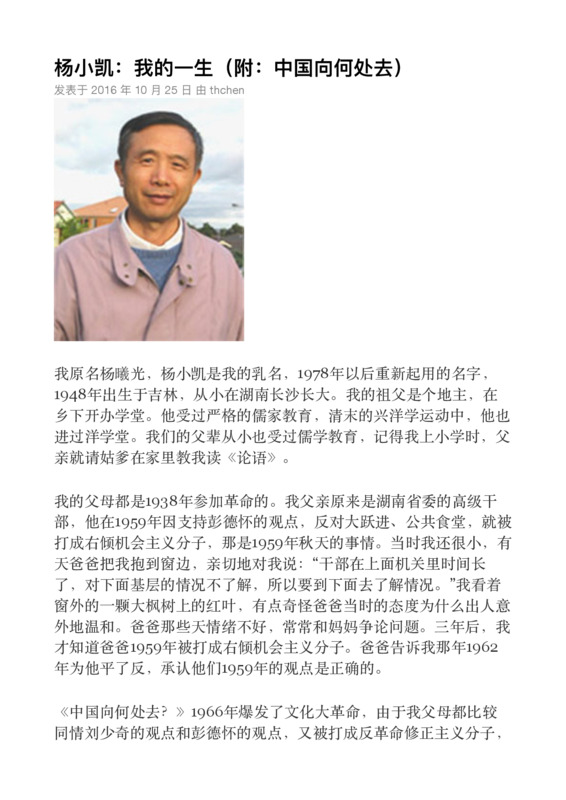

Article

My Life: China's Direction

When the Cultural Revolution broke out, Yang Xiaokai was a senior high school student at No. 1 Middle School in Changsha. On January 12, 1968, he published an article entitled "Where is China Going?" which systematically put forward the ideas of the "ultra-leftist" Red Guards, criticized the privileged bureaucratic class in China, and advocated for the establishment of a Chinese People's Commune based on the principles of the Paris Commune. Yang Xiaokai recalled that his parents were beaten because they sympathized with Liu Shaoqi's and Peng Dehuai's views, and that he was discriminated against at school and could not join the Red Guards. As a result, he joined the rebel faction to oppose the theory of descent. Yang Xiaokai was later sentenced to 10 years' imprisonment for this article. Yang Xiaokai died in 2004. This article is a retrospective of his life.

Book

My Mother :Gao Yaojie

Author Eva writes about her relationship with Gao Yaojie, a Chinese doctor. Dr. Gao Yaojie, who was severely repressed by the Chinese government for exposing the mass infection of Chinese farmers in Henan Province, China, by selling their blood, had no choice but to leave China at the age of 78 and go into exile in the United States. The dissemination of her story is strictly forbidden in China. In this book, author Eva describes Gao Yaojie's noble heart, her story, and her experiences.

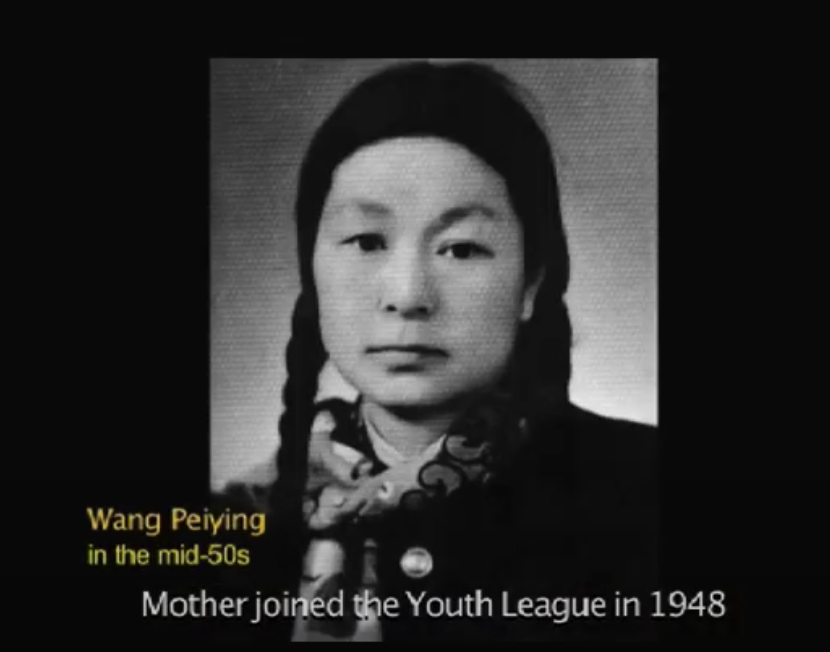

Film and Video

My Mother Wang Peiying

On January 27, 1970, Wang Peiying, a cleaner at a kindergarten in Beijing, was sentenced for counter-revolutionary crimes at a 100,000-person public trial held at the Workers' Stadium in Beijing. She was then taken to the execution ground along with a dozen other political prisoners to be executed by firing squad. Wang Peiying was strangled to death in the torture wagon because she preferred to die rather than give in and shout slogans. Forty years later, her daughter, Kexin, began to search for her mother's story. Through her mother's coworkers, friends in distress, and the task force, she gradually discovers her mother's experience as an active counterrevolutionary. In order to protect her conscience, Wang Peiying chose to stand up for her dignity and freedom to tell the truth, and willingly endured brutal torture. The documentary reflects the brutality of the Cultural Revolution and the destruction of humanity.

Film and Video

New Citizens’ Trial

In late January 2014, on the eve of the Lunar New Year, Xu Zhiyong, Zhao Changqing, Ding Jiaxi and other advocates of the New Citizens’ Movement were charged with "gathering a crowd to disrupt order in a public place." The case was heard for the first time in courts at different levels in Beijing. This film intersperses on-site records with interviews with defense lawyer Zhang Qingfang, scholar Guo Yuhua, entrepreneur Wang Ying, and others to present citizens' understanding of the New Citizens' Movement.

This series of films are in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Book

Newly Discovered Mao, The: Volume I

Author Wang Ruoshui spent his early years studying philosophy at Peking University. He served as deputy editor-in-chief of the Communist Party newspaper “People's Daily” and was able to participate in high-level ideological discussions, gaining a deep understanding of Mao Zedong as a person and of his thought. He was one of the rare intellectuals within the CCP system who had an independent personality as well as the ability to think for himself. After his death from cancer, his wife, Feng Yuan, helped put together this posthumous book. Published by Ming Pao Press in 2002, it has been described as "the first and most comprehensive and in-depth discussion of Mao Zedong and his thought."

Book

Newly Discovered Mao, The: Volume II

Author Wang Ruoshui spent his early years studying philosophy at Peking University. He served as deputy editor-in-chief of the Communist Party newspaper "People's Daily" and was able to participate in high-level ideological discussions, gaining a deep understanding of Mao Zedong as a person and his thought. He was one of the rare intellectuals within the CCP system who had an independent personality as well as the ability to think for himself. After his death from cancer, his wife, Feng Yuan, put together this posthumous book. Published by Ming Pao Press in 2002, it has been described as "the first and most comprehensive and in-depth discussion of Mao Zedong and his thought.

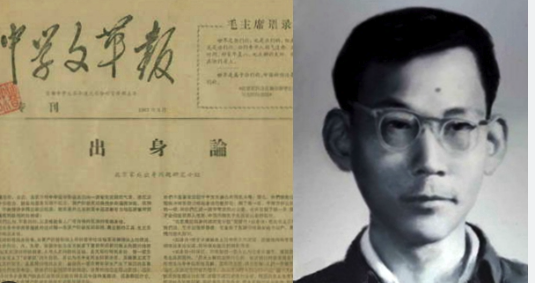

Article

On Family Background

Yu Luoke (May 1, 1942 - March 5, 1970): Worker, freelance writer, and public intellectual.

Yu was born into an educated family in northeastern China, which for a period of time was under Japanese occupation. His father studied on a state scholarship in Waseda University in Tokyo, while his mother came from a wealthy family in Beijing and studied business at Tokyo Girls High School. When the two returned to China, they went into business, married, and had three children.

When the CCP took power, the family was declared part of the “bourgeois class” and like other “black elements”--classes of people who the party declared to be enemies–was persecuted. The father was arrested in 1952 on charges of tax evasion and released. In 1957, Yu Luoke’s parents were declared Rightists and sent to labor camps. In 1959, Yu graduated from high school with highest honors but as the offspring of an undesirable class was not permitted to attend university. In 1961, he was allowed to work on a farm in a Beijing suburb, where he realized that class identity was also important in rural China–landlords and their children were even beaten to death. In 1964 he returned to the city and apprenticed at a machinery factory. Yu realized that he was part of an untouchable caste in Maoist China and would be condemned forever, no matter what he believed or how hard he worked.

These experiences were the genesis of Yu’s essay, which became one of the most famous texts of the Mao era. Yu wrote it at the start of the Cultural Revolution. The ten-thousand character essay is called chushenglun, or “On Family Background” (sometimes translated as “On Class Origins"). In it, he warned that the “five black categories'' were becoming a permanent underclass, while China’s rulers were from the hongwulei, or “five red categories:” poor and lower-middle peasants, workers, revolutionary soldiers, revolutionary officials, and revolutionary martyrs, including their family members, children, and grandchildren. He warned of a new ruling class based on bloodlines.

The essay was published in a journal that Yu and his brother Yu Luowen called the "Journal of Secondary School Cultural Revolution." In January 1967, about thirty thousand copies were printed, and the young men began distributing them around the capital, selling them for two cents a copy. They sold out in a few hours. In February, they printed another eighty thousand copies.

Soon, hundreds of letters each day arrived at Yu Luoke’s local post office—so many that he had to go collect them in person. The missives detailed how the Communists’ policies had caused them to suffer. People traveled from across China to visit them at their home, excited that someone finally had uncovered how the Chinese Communist Party ruled. The editorial board was expanded to twenty people, and the group sponsored debates and seminars.

The Journal was closed down in April 1967. Yu Luoke began to write on economic inequality. In January 1968, he was arrested. Two years later, on 5 March 1970, Yu was executed by firing squad at Beijing Workers Stadium.

Film and Video

Onlookers

People from all over China rush to the scene of China's trial of Bo Xilai, the former Chongqing Party Secretary of the Communist Party of China. The trial took place in August 2013 at the Jinan Intermediate People's Court in Shandong Province. Reporter Liu Xiangnan captured the scene.

Article

Operation Yellow Bird

After the bloody suppression of the June 4 Democracy Movement, the Chinese Communist Party went on a massive manhunt for the key figures of the movement. Some Hong Kong people organized a secret channel to help pro-democracy activists escape from the Mainland, codenamed "Operation Yellow Bird." The author of this book, Jiang Xun, is a veteran of the media and describes in detail how the "Yellow Bird Operation" took place.

Article

Oral Interviews with Global Feminists

As one of China's foremost feminist activists and thinkers, Ai was interviewed by the Global Feminisms Project at the University of Michigan. In this interview, Ai talks about her upbringing as well as about the current state of feminism in China and its outlook.

Film and Video

Our Children

This documentary records the stories of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake. The narrators mainly consist of the parents of students who fell victim to the earthquake, and the film is interspersed with comments from media workers, independent scholars, internet authors, geologists, and environmental protection and legal workers. They expressed their views on the Sichuan earthquake from different perspectives.

This film is in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Book

Pastor Wang Yi's Anthology: Carrying the Cross - A History of Chinese Family Churches

Wang Yi, of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, is a well-known Chinese intellectual who later became a pastor. The Early Rain Reformed Church that he led was one of the most famous unregistered churches in China. The church occupied the floor of an office building in Chengdu and had its own bookstore, seminary, and pre-school. It regularly had services of hundreds of people. Later, the church had internal conflicts, while at the same time Wang became more outspoken in his criticism of the government. In 2018, he criticized Xi Jinping for abolishing term limits and allowing himself to become ruler of China for life. Pastor Wang was sentenced to nine years in prison in 2019.

This book is based on the recordings of Pastor Wang's classes at Early Rain in 2018. The first five chapters were reviewed by Pastor Wang himself, but he was arrested before he could complete the review of the last five chapters. The essays cover key issues that concerned Wang, including the role of the church in China as a city on the hill, the role of the Reform church in China, and the history of unregistered churches in China.

Book

Personal experiences of political movements

This book is a collection of many authors, most of whom were former senior officials of the Communist Party of China, such as Li Rui, Xiao Ke and others. Through the author's recollections, we can learn about the political movements of the Mao Zedong era, including the Cultural Revolution, the Anti-Rightist Movement, etc., as well as the details of many unjust cases, such as the Hu Feng case, which is quite convincing. This book was published by the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau Press in mainland China in 1998.

Film and Video

Postcard

After retiring from her job as a cadre, Wang Lihong fulfilled what she saw as her civic responsibility to become more active in women’s rights in China, especially the protection of their legal rights. In 2009-2010, she became involved in the “Fujian Netizen Case,” which resulted in the arrest of three human rights activists, who all sought to investigate the death of a 25-year-old women believed to have been murdered in a gang rape by men associated with the local police. Wang Lihong wrote letters to the General Secretary of the Fujian Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China every day for nine consecutive days, calling on the authorities to let them go home for the New Year. For this reason, she was criminally detained by the authorities in March 2011 on suspicion of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble." The case was heard by the Beijing, Chaoyang District People's Court on August 12; nearly a month later, on September 9, the court issued a guilty verdict and sentenced Wang Lihong to nine months in prison. The film documents her case, and raises questions about the accountability of the local government and police. Another one of Ai Xiaoming’s films, “Let the Sunshine Reach the Earth,” documents Wang Lihong’s trial process in more detail.

This film is in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.