Explore the collection

Showing 91 items in the collection

91 items

Book

Liushahe Essay

Liushahe is a famous Chinese writer and scholar, who entered Sichuan University in the fall of 1949, and was criticized and stigmatized nationwide during the 1957 Anti-Rightist Movement for his work *Grass and Trees* named by Mao Zedong himself, and then subjected to a variety of labor reforms (building roads during the day and sawing wood in the evening) for a cumulative total of 20 years. In 1979, he was transferred back to the Sichuan Provincial Literature Federation. Since 1985 he has been writing full-time, and has published a number of books, including *Essays on the Liusha River*. This book was published by Sichuan Literature and Art Publishing House in 1995. Many of the essays are related to his experiences when he was under labor reform. In November 2019, Liushahe passed away in Chengdu at the age of 88 due to illness.

Book

Lushan meeting factual record

This book is a historical record of the 1959 Lushan Conference written by Li Rui. Based on the author's personal experience and the literature of the relevant departments of the Communist Party of China, the author has recorded the important points and events before and after the meeting. The first edition of this book was published in April 1989 by the Spring and Autumn Publishing House and Hunan Education Publishing House in mainland China; the updated edition was published in June 1994 by Henan People's Publishing House.

Book

Man-Made Disasters: The Great Leap Forward and the Great Famine.

The author of this book, Ding Shu, is a Chinese scholar living in the United States. Published in 1991 by the Hong Kong-based "Nineties Magazine", this book is the first monograph on the Great Famine in China. It has been described by some scholars as the cornerstone of the study of the Great Famine in China. The book was later updated and reprinted. The book starts from the cooperative movement and moves on to the Great Leap Forward, the Great Iron and Steel Refining, the People's Commune, the Satellite Release and the Great Communist Wind; then, it turns to the Lushan Conference against right-leaning as well as the 7,000 People's Congress in 1962. The author collected almost all the information that could be collected at that time and summarized it to describe the situation of this great famine and its causes and consequences. The content of this book is from the website of the Chinese blog "Bianchengsuixiang" (编程随想).

Book

Mao in Power (1949-1976)

The author of this book, Shan Shaojie, is a scholar from mainland China. For several years, he wrote this book from an independent position. Former political secretary of Mao Zedong, Li Rui, and Princeton University professor, Yu Yingshi, wrote the foreword for this book. In addition to a systematic account of the Maoist era, Shan Shaojie's book "Mao in Power" emphasizes that almost all members of the Communist Party's highest decision-making echelons, with the exception of Mao Zedong, made efforts, in varying degrees and successively, to stop Mao's insanity. Moreover, they took turns to resist and ultimately to leave Mao alone, but did not really stop Mao's madness. This book was published by Linking Publishing in 2001 and has been reprinted several times.

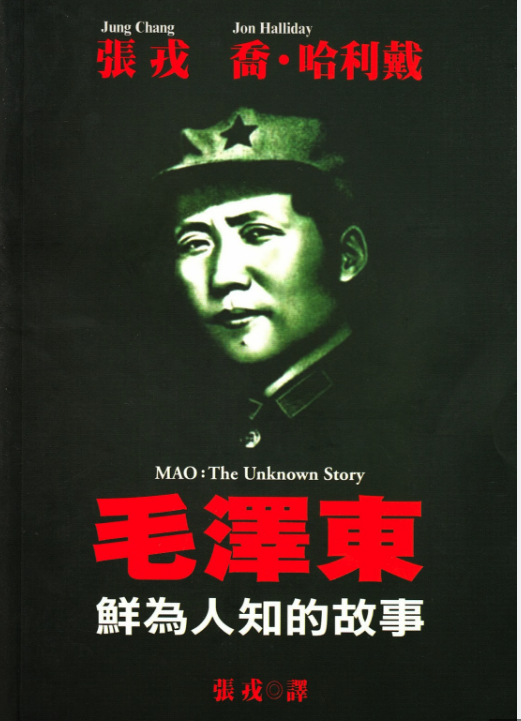

Book

Mao: The Unknown Story

This book presents the dramatic life of Mao Zedong, revealing a wealth of unheard-of facts: why Mao joined the Communist Party, how he came to sit at the top of the Chinese Communist Party, and how he seized China step by step. Writers Jung Chang and her husband Jon Halliday took ten years to complete this book, interviewing hundreds of Mao's relatives and friends, Chinese and foreign informants and witnesses who worked and interacted with Mao as well as dignitaries from various countries.

Purchase link:https://www.amazon.com/Mao-Story-Jung-Chang/dp/0679746323.

Article

Memorandum on "Three Years of Natural Disasters"

The years 1959-1961 were very unusual in the history of disasters in China and the world in the 20th century. Anyone who has experienced it will recall the starvation years and the days when people starved to death everywhere. However, due to official concealment and denial, the number of people who died in this disaster has never been officially announced.

The purpose of Jin Hui's article is to estimate the number of unnatural deaths during the three years of the 1959-1961 disaster in China. Based on public data released by the authoritative National Bureau of Statistics in China Jin concludes that about 40 million people died, which roughly matches studies by foreign scholars, who have estimated up to 45 million.

Film and Video

Memory of Lin Zhao

Independent director Tiger Temple began shooting this film in 2010 and completed it in 2012, with subsequent revisions. The film features interviews with Lin Zhao's former lover Gan Cui as well as interviews with several independent scholars such as Qian Liqun and Cui Weiping. It is a powerful addition to Lin Zhao's memory. This film was selected as one of the top 20 finalists in the 2012 Sunshine Chinese Documentary Awards.

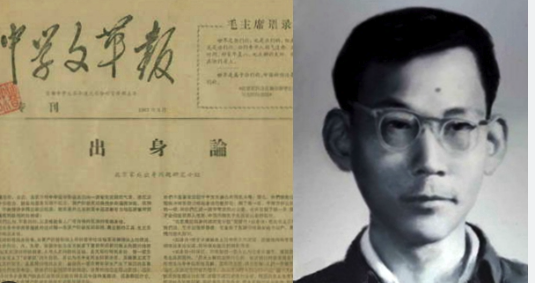

Article

On Family Background

Yu Luoke (May 1, 1942 - March 5, 1970): Worker, freelance writer, and public intellectual.

Yu was born into an educated family in northeastern China, which for a period of time was under Japanese occupation. His father studied on a state scholarship in Waseda University in Tokyo, while his mother came from a wealthy family in Beijing and studied business at Tokyo Girls High School. When the two returned to China, they went into business, married, and had three children.

When the CCP took power, the family was declared part of the “bourgeois class” and like other “black elements”--classes of people who the party declared to be enemies–was persecuted. The father was arrested in 1952 on charges of tax evasion and released. In 1957, Yu Luoke’s parents were declared Rightists and sent to labor camps. In 1959, Yu graduated from high school with highest honors but as the offspring of an undesirable class was not permitted to attend university. In 1961, he was allowed to work on a farm in a Beijing suburb, where he realized that class identity was also important in rural China–landlords and their children were even beaten to death. In 1964 he returned to the city and apprenticed at a machinery factory. Yu realized that he was part of an untouchable caste in Maoist China and would be condemned forever, no matter what he believed or how hard he worked.

These experiences were the genesis of Yu’s essay, which became one of the most famous texts of the Mao era. Yu wrote it at the start of the Cultural Revolution. The ten-thousand character essay is called chushenglun, or “On Family Background” (sometimes translated as “On Class Origins"). In it, he warned that the “five black categories'' were becoming a permanent underclass, while China’s rulers were from the hongwulei, or “five red categories:” poor and lower-middle peasants, workers, revolutionary soldiers, revolutionary officials, and revolutionary martyrs, including their family members, children, and grandchildren. He warned of a new ruling class based on bloodlines.

The essay was published in a journal that Yu and his brother Yu Luowen called the "Journal of Secondary School Cultural Revolution." In January 1967, about thirty thousand copies were printed, and the young men began distributing them around the capital, selling them for two cents a copy. They sold out in a few hours. In February, they printed another eighty thousand copies.

Soon, hundreds of letters each day arrived at Yu Luoke’s local post office—so many that he had to go collect them in person. The missives detailed how the Communists’ policies had caused them to suffer. People traveled from across China to visit them at their home, excited that someone finally had uncovered how the Chinese Communist Party ruled. The editorial board was expanded to twenty people, and the group sponsored debates and seminars.

The Journal was closed down in April 1967. Yu Luoke began to write on economic inequality. In January 1968, he was arrested. Two years later, on 5 March 1970, Yu was executed by firing squad at Beijing Workers Stadium.

Book

Pastor Wang Yi's Anthology: Carrying the Cross - A History of Chinese Family Churches

Wang Yi, of Chengdu, Sichuan Province, is a well-known Chinese intellectual who later became a pastor. The Early Rain Reformed Church that he led was one of the most famous unregistered churches in China. The church occupied the floor of an office building in Chengdu and had its own bookstore, seminary, and pre-school. It regularly had services of hundreds of people. Later, the church had internal conflicts, while at the same time Wang became more outspoken in his criticism of the government. In 2018, he criticized Xi Jinping for abolishing term limits and allowing himself to become ruler of China for life. Pastor Wang was sentenced to nine years in prison in 2019.

This book is based on the recordings of Pastor Wang's classes at Early Rain in 2018. The first five chapters were reviewed by Pastor Wang himself, but he was arrested before he could complete the review of the last five chapters. The essays cover key issues that concerned Wang, including the role of the church in China as a city on the hill, the role of the Reform church in China, and the history of unregistered churches in China.

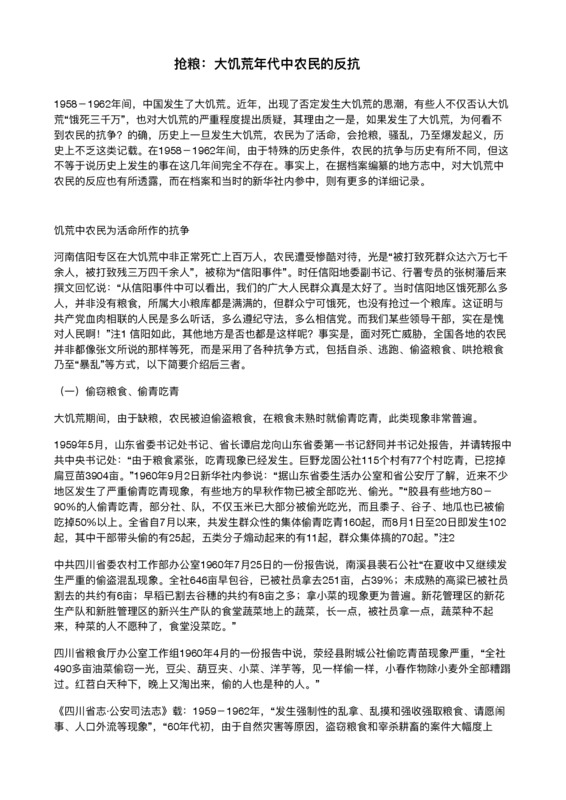

Article

Peasant resistance in the years of the Great Famine

Even today in China, some people have been trying to deny that there was a great famine in 1960. One of the reasons is: If there was a great famine, why did we not see the peasants' resistance? It is true that historically, in the event of a famine, peasants would loot grain, riot, and even break out in revolt in order to survive, but during the period 1958-1962, due to the special historical conditions, it seems that there is no record of peasants' resistance. But this was not the case. This article collects facts to prove the existence of peasant resistance.

Film and Video

Postcard

After retiring from her job as a cadre, Wang Lihong fulfilled what she saw as her civic responsibility to become more active in women’s rights in China, especially the protection of their legal rights. In 2009-2010, she became involved in the “Fujian Netizen Case,” which resulted in the arrest of three human rights activists, who all sought to investigate the death of a 25-year-old women believed to have been murdered in a gang rape by men associated with the local police. Wang Lihong wrote letters to the General Secretary of the Fujian Provincial Committee of the Communist Party of China every day for nine consecutive days, calling on the authorities to let them go home for the New Year. For this reason, she was criminally detained by the authorities in March 2011 on suspicion of "picking quarrels and provoking trouble." The case was heard by the Beijing, Chaoyang District People's Court on August 12; nearly a month later, on September 9, the court issued a guilty verdict and sentenced Wang Lihong to nine months in prison. The film documents her case, and raises questions about the accountability of the local government and police. Another one of Ai Xiaoming’s films, “Let the Sunshine Reach the Earth,” documents Wang Lihong’s trial process in more detail.

This film is in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Film and Video

Red Art

This documentary interviews painters, Red Guards, as well as current collectors and researchers in China and the United Kingdom. It presents the emergence, spread, and impact of the propaganda posters during the Cultural Revolution. The film includes interviews with Liu Chunhua, the author of Chairman Mao Goes to Anyuan, Guangzhou painter Li Xingtao, Guangzhou old Red Guard Zhou Jineng, and others. Art museum personnels, art critics, journalists, professors, and researchers in both China and the United Kingdom speak about their understanding of the art of the Cultural Revolution from various perspectives.

This film is in Chinese with both English and Chinese subtitles.

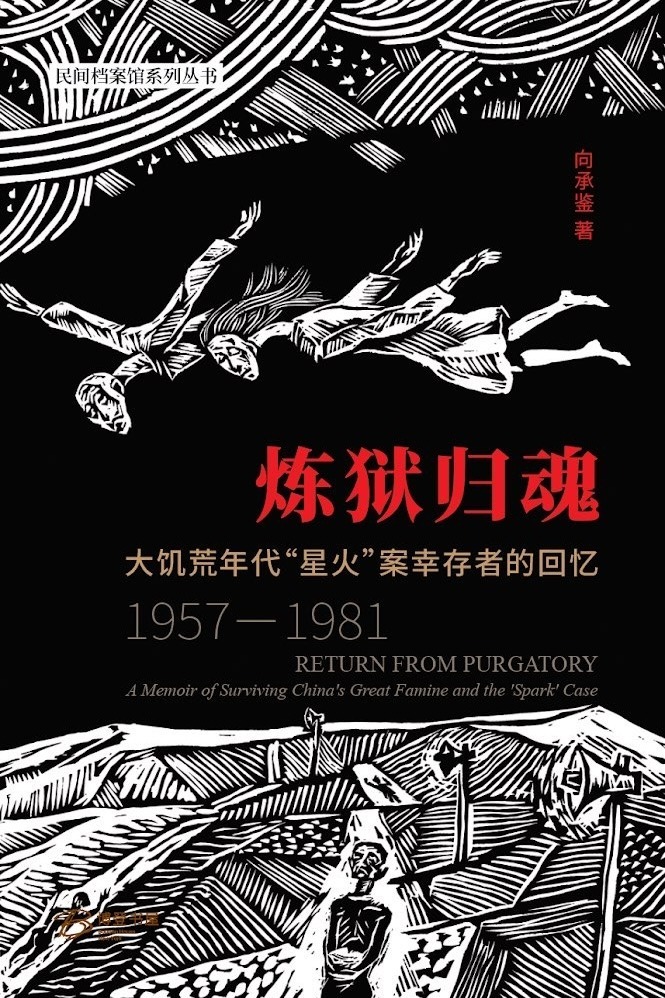

book

Return of the Soul from Purgatory: Memoirs of a Survivor of the "Sparks" Case from the Great Famine Era

In 1960, a group of faculty and students from Lanzhou University, who had been labeled Rightists and sent down to rural areas in Tianshui, Gansu, personally experienced the Great Famine. They self-published <i>Spark</i> magazine to expose and criticize the totalitarian rule that led to this catastrophe.<i>Spark</i> only published one issue before its participants were arrested and labeled as a counterrevolutionary group. Many were sentenced to long prison terms, and some were even executed. <a href=“http://108.160.154.72/s/china-unofficial/item/1759#lg=1&slide=0”>The first issue of <i>Spark</i> and more information about the "Spark Case" can be read here</a>.

<i>Return from Purgatory: A Survivor’s Memoir of the ‘Spark Case’ in the Great Famine Years (1957–1981)</i> is the autobiography of Xiang Chengjian, a key participant in <i>Spark</i> magazine. At the time, he and another student were responsible for printing the first issue, and he contributed six articles to <i>Spark</i>. Due to his involvement, he was sentenced to 18 years in prison for his role in the Spark case and was not rehabilitated until the early 1980s.

This memoir is divided into three sections, with a total of thirteen chapters spanning over 350,000 characters. It documents Xiang’s journey from being labeled a Rightist and sent to perform forced labor, to his arrest and 19-year imprisonment for his involvement in <i>Spark</i>, and finally to his struggle for rehabilitation and efforts to rebuild his life after release. In the book’s preface, scholar Ai Xiaoming offers the following assessment:

"Xiang Chengjian’s memoir holds significant value for the study of the intellectual history of contemporary China. First, it serves as another important testimony of the “Spark Case”, following Tan Chanxue’s memoir <i><a href=“”>Sparks: A Chronicle of the Rightist Counter-Revolutionary Group at Lanzhou University</a></i>, making it a crucial historical document on this act of resistance. The author reconstructs the social context before and after the case and describes how the young intellectuals behind <i>Spark</i> bravely challenged totalitarian rule. Second, the book provides a detailed account of labor camps in western China, with the author documenting his 18 years of forced labor in Gansu and Qinghai, unveiling a western chapter of China’s Gulag system. Third, it is a deeply personal intellectual history of a resister, showing the immense suffering, trials of life and death, and personal resilience under the crushing force of state violence."

The book’s appendix includes Xiang Chengjian’s six articles for <i>Spark</i>, an in-depth investigative report on him by journalist Jiang Xue, and a chronological record of the Spark Case compiled by Ai Xiaoming.

<i>Return from Purgatory</i> is published by Borden Press in New York and is the first book in the “People’s Archives Series”, published by the China Unofficial Archives. The author, Xiang Chengjian, has generously authorized the archive to share the book’s digital edition. Readers are encouraged to purchase the book to support the author and publisher.

Film and Video

Spark

<i>Spark</i> tells the story of a group of young intellectuals who risked their lives to voice their opinions about the Chinese Communist Party in the 1950s and 1960s. Following the Hundred Flowers Campaign of 1957, many intellectuals were branded as Rightists and banished to work and live in rural China. A group of students from Lanzhou University were among those sent to the countryside. There, they witnessed mass famine which resulted from government policies to collectivize agriculture and force industrialization in rural China. Shocked and angered by the government’s lack of response to the Great Famine, these students banded together to publish <i>Spark</i>, an underground magazine that sought to alert the Chinese population of the unfolding famine. The first issue, printed in 1960, included poems and articles analyzing the root causes of failed policies. However, as the first issue of <i>Spark</i> was mailed and the second issue was edited, many of these students, along with locals who supported the team, were arrested. Some of the key members of the publication were sentenced to life imprisonment and later executed, while others spent decades in labor camps.

In this 2014 documentary, Hu Jie uncovers the stories of the people involved in the publication of <i>Spark</i>. He conducts interviews with former members of the magazine who survived persecution, and also shows footage of the manuscripts of the magazine. A digital copy of the original manuscript of the first volume of <i>Spark</i> is also held on our website.

This film was awarded the Special Jury Prize for Chinese Documentary at the 2014 Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival and the Award of Excellence in the Asian Competition. Later, it won the Independent Spirit Award at the Beijing Independent Film Festival.

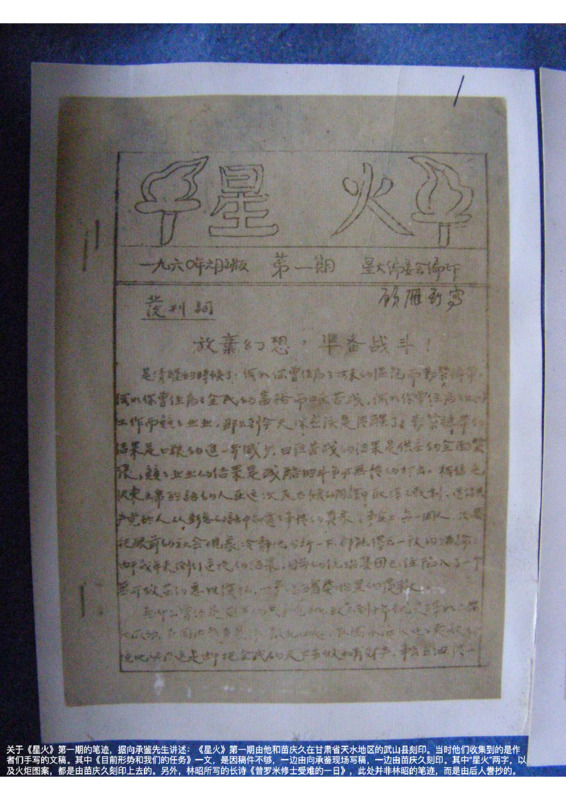

Periodicals

Spark, Issue 1

<i>Spark</i> was an underground magazine that appeared in the Tianshui area of Gansu Province in northwestern China during the 1959-1961 Great Famine. The magazine was lost for decades but in the late 1990s began to be republished electronically, becoming the basis of documentary films, essays, and books.

In 1959, the Great Famine was spreading across China. It was witnessed by a group of Lanzhou University students who had been branded as Rightists and sent down to labor in the rural area of Tianshui. They saw countless peasants dying of hunger, and witnessed cannibalism.

Led by Zhang Chunyuan, a history student at Lanzhou University, they founded <i>Spark</i> in the hope of alerting people to the unfolding disaster and analyzing its root causes. The students pooled their money to buy a mimeograph machine, carved their own wax plates, and printed the first issue. The thirty-page publication featured Lin Zhao's long poem, "A Day in Prometheus's Passion." The first issue also featured articles, such as "The Current Situation and Duty," which dissected the tragic situation of society at that time and hoped that the revolution would be initiated by the Communist Party from within.

The students planned to send the magazine to the leaders of the provinces and cities with a view to correcting their mistakes. But before the first issue of Spark was mailed and while the second issue was still being edited, on September 30, 1960, these students in Wushan and Tianshui were arrested, along with dozens of local peasants who knew and supported them. Among them: Zhang Chunyuan was sentenced to life imprisonment and later executed; Du Yinghua, deputy secretary of the Wushan County Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, was sentenced to five years' imprisonment for having interacted with the students, and later executed. Lin Zhao was detained and also executed. Other key members, such as Gu Yan, Tan Chanxue, and Xiang Chengjian, were all sentenced to long years in labor camps.

In the 1990s, Tan Chanxue devoted herself to researching historical information and figures to bring this history to life. She found in her personnel file (<i>dan'an</i>)photographs of the magazine, as well as self-confessions and other evidence used in the students' trial. Eventually, the photos were collated into PDFs, which began to circulate around China.

Editors' note: This site the original handwritten version and a PDF of all the articles from the first issue of <i>Spark</i>. We will also make available transcripts of the essays in Chinese and are searching for volunteers to translate the texts into English. Please contact us if you're interested in helping!

Book

Sparks: A Chronicle of the Rightist Counter-Revolutionary Group at Lanzhou University

During the worst years of the 1960 famine, a group of teachers and students at Lanzhou University decided to publish an underground publication, <i>Spark</i>, to alert Chinese people to the growing disaster and expose the authoritarianism of the Chinese Communist Party. Only two issues of this underground publication were printed before it was broken up as a counter-revolutionary group case and 43 people were arrested.

The author of this book, Tan Chanxue, was a key participant and helped save the memory of <i>Spark</i> from being lost. Tan was the girlfriend of Zhang Chunyuan, the magazine's founder, and participated in key moments of the magazine's short lifespan. She was sentenced to 14 years in prison, but was later released and rehabilitated, and taught at the Jiuquan Teachers' Training School. In 1982, she was transferred to the Dunhuang Research Institute as an associate researcher, and retired in 1998, settling in Shanghai.

It is largely through Tan's efforts that we know about <i>Spark</i>. She was able to look into her personnel file (<i>dang'an</i>), where she discovered the issues of the magazine, as well as confessions of the people arrested, and even her love letters to Zhang. She photographed this material and later it was turned into PDFs, which circulated around China starting in the late 1990s, helping to inspire books and movies.

Article

Special Collections |Famine and Counties (7): The Great Famine in Xili County around 1960

Around 1960, Xili County experienced a famine unprecedented in modern history, resulting in massive population deaths and an exodus, with 44,608 deaths in the county in 1960 alone (43,793 according to provincial statistics). In early 1961, the momentum of population deaths continued to develop, with 525 deaths in January, rising to 729 in February. Along with the massive population deaths, various diseases began to spread. Famine and disease caused a massive exodus of population. From 1958 to 1960 the exodus of population from the county reached 14,241 people. Also due to the death and exodus of population, 170,000 acres of land in the county were left barren, only one commune of Luoyu at that time had more than 20,000 acres.

Article

Special Collections |Famine and County (2): Guizhou Meitan Incident

In Meitan County, Guizhou Province, from November 1959 to early April 1960, more than 120,000 people starved to death in five months. The deaths accounted for more than 20 percent of the county's total population and 22 percent of the agricultural population. During the incident, 2,938 families died in the county, 4,737 orphans and widows were left behind, and 4,737 peasants went out to escape. The most tragic and horrible thing to witness was incidents of cannibalism. The author participated in the compilation of "Meitan County Records," read the relevant historical materials, and organized this article to reproduce the real history for future generations to learn from.