Explore the collection

Showing 26 items in the collection

26 items

Book

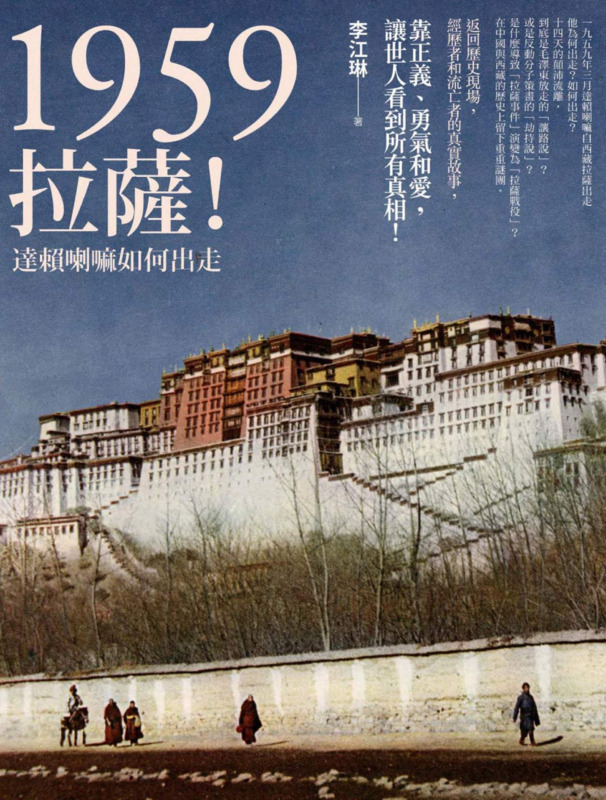

Tibet in Agony: Lhasa 1959

Traveling Chinese history scholar Li Jianglin began working on the Tibet issue in 2004. She has traveled to India every year in search of Tibetan refugees, visited 14 Tibetan refugee settlements in India and Nepal, contacted more than 200 exiled Tibetans from the three regions of Tibet, and personally interviewed the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, the seat of the Tibetan government-in-exile, in 2008. In 2010, Li Jianglin completed her book <i>Lhasa 1959!</i> by drawing on interviews, information searches, and rare historical photographs provided by the Tibetan government in exile, in the hope of reconstructing the little-known history of the Dalai Lama's departure from Tibet in 1959. The book was published by Taiwan's Lianjing Publishing House in 2010 and reprinted in 2016.

Book

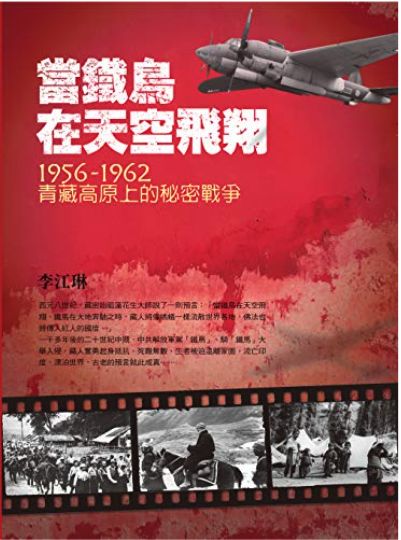

When the Iron Bird Flies: China's Secret War in Tibet

Around the eighth century A.D., the founder of Tibetan Buddhism, Guru Rinpoche, prophesied, "When the iron bird flies in the sky and the iron horse runs on the earth, the Tibetans will be dispersed all over the world like ants, and the Buddha's Dharma will be spread into the land of the red people." More than 1,000 years later, in the middle of the 20th century, the Chinese Communist Party drove the "iron bird" across the sky and rode the "iron horse" across the plateau. The Tibetans courageously rose up to resist resulting in with countless deaths countless deaths. Those who survived were forced to leave their homeland and live in exile in India, drifting around the world. Thus, the prophecy came true. From a military point of view, the Tibetan war in Tibet was a victory, but it received only minimal publicity. The official version of the Party's history is either vague or evasive about the bloody massacre during the entry into Tibet, attempting to cover it up by "suppressing armed rebellion" and "purging counter-revolutionaries". More than sixty years later, this war has yet to be demystified. Li Jianglin, an independent scholar, was moved by the tragedy of the war and the plight of the Tibetans, and endeavored to restore the historical facts. Since 2004, she has devoted herself to research, visiting hundreds of Tibetan elders, searching for tens of thousands of historical materials, collecting military archives, and comparing them with the official published materials of the Communist Party of China, in order to present memories of past, little by little.

Film and Video

Why Are Flowers So Red

This film follows the stories of environmental activist Tan Zuoren and artist Ai Weiwei. In July 2009, Tan Zuoren was charged with the crime of “Inciting subversion of state power,” and his trial was held in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Ai Weiwei was invited by Tan’s lawyer to testify in court, but the night before the trial, he was assaulted by the police and detained in a hotel. To everyone’s surprise, Ai turned on the tape recorder before the police entered his residence and managed to record the incident. Later, Ai and his colleagues released a documentary about this incident, titled “Disturbing the Peace” (or “Laoma Tihua”).

This film interviews the people behind the scenes of “Disturbing the Peace,” including the director, photographers, editors, and audiences of the film, who discuss the relationship between citizens and government authority.

This series of films are in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Article

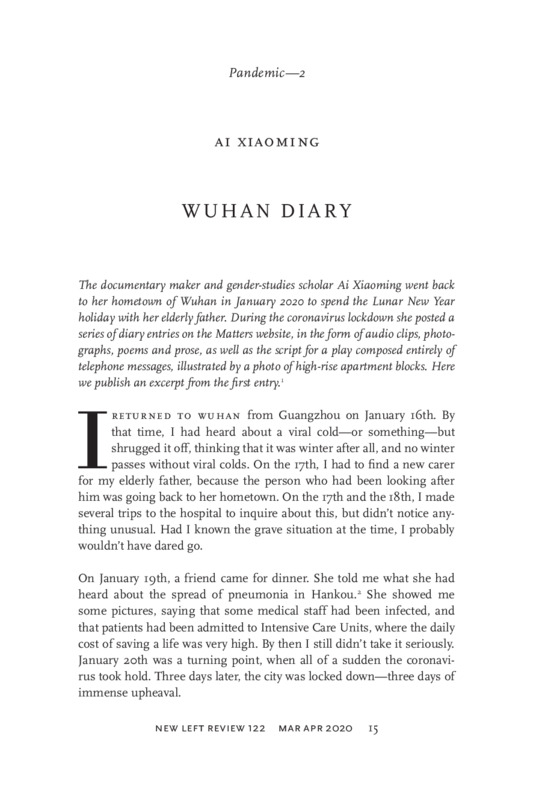

Wuhan Diary

This collection of diary entries by Wuhan-based filmmaker and activist Ai Xiaoming showcases her life during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, from February to March 2020. In these diary entries, Ai shares the daily challenges which many Chinese people grappled with, as well as their hopes and questions for the government and Chinese society at large. Her diary also examines problems regarding the expanding powers of the Chinese government. The first entry of Ai’s diary was published in English by the New Left Review, which can be found here:

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii122/articles/xiaoming-ai-wuhan-diary.

Book

Wuhan Diary: Dispatches from a Quarantined City

This book is a collection of diary entries written in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic by Fang Fang, a Chinese writer and advocate of the working poor in China. In these diary entries, Fang Fang documents the various daily difficulties faced by her and other Wuhan residents from January to March 2020. In this book, she also ponders the implications of official policies with regard to the pandemic and the way in which the public and the government have responded to the outbreak of COVID-19. These entries tell us about the hopes and fears of the people of Wuhan during the early stage of COVID-19, and adds to our understanding of public opinion and government policies in China in the 2020s. The diaries were published in Chinese, and have also been translated by Michael Berry into English and published by Harper Collins Publishers.

You can purchase the English version of the book using <a href="https://www.harpercollins.com/products/wuhan-diary-fang-fangmichael-berry?variant=40153409749026">this link</a> .

Film and Video

Beijing's Petition Village

In China, individuals can complain to higher authorities about corrupt government processes or officials through the petition system. The form of extrajudicial action, also known as "Letters and Visits" (from the Chinese xinfang and shangfang), dates back to the imperial era. If people believe that a judicial case was concluded not in accordance with law or that local government officials illegally violated his rights, they can bring it to authorities in a more elevated level of government for hearing, re-decide it and punish the lower level authorities. Every level and office in the Chinese government has a bureau of “Letters and Visits.” What sets China’s petitioning system apart is that it is a formal procedure—and as Zhao Liang's documentary shows, the system is largely a failure.

A residential area near Beijing South Railway Station was once home to tens of thousands of residents from all over the country. Known as “Petition Village,” its bungalows and shacks were demolished by authorities several times, but many petitioners still clung to the land in search of a clear future. _Beijing Petition Village_ portrays the village in the midst of this upheaval, focusing on the thousands of civilians who travel from the provinces to lodge their complaints in person with the highest petitioning body, the State Bureau of Letters and Visits Calls in the province, only to repeatedly get the brush-off by state officials. Ultimately, in 2007, Petition Village was demolished for good.

The film went on to win the Halekulani Golden Orchid Award for Best Documentary Film at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival, and a Humanitarian Award for Documentaries at the 34th Hong Kong Film Awards.