Explore the collection

Showing 44 items in the collection

44 items

Article

Yang Kuisong: A Study of New China's "Counter-Revolutionary Suppression" Campaign

How many people were "killed," "imprisoned," and "controlled" in the whole "anti-revolution" campaign? Mao Zedong later said that 700,000 people were killed, 1.2 million were imprisoned, and 1.2 million were put under control. Mao's statement was naturally based on a report made in January 1954 by Xu Zirong, deputy minister of public security. Xu reported at the time that since the anti-revolution campaign, the country had arrested more than 262,000, of which "more than 712,000 counter-revolutionaries were killed, more than 12,900,000 were imprisoned, and 1,200,000 were put under control, and more than 380,000 were released through education because their crimes were not considered serious after their arrest." (3) Taking the figure of 712,000 executed, it already amounts to one and two-fourths thousandths of one percent of the country's 500 million people at that time. This figure is obviously much higher than the one-thousandth of a percent level originally envisioned by Mao Zedong.

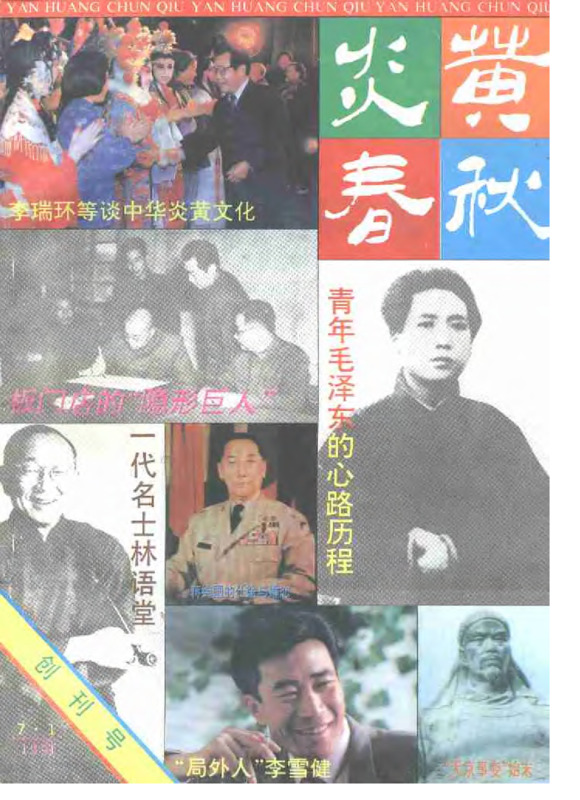

Yanhuang Chunqiu

This magazine was one of most important alternative history journals. It was founded in 1991 by a liberal faction in the CCP, with the help of people such as Xiao Ke, a general in the PLA, and Du Daozheng, a Chinese journalist who once served as head of Guangming Daily and the head of the National Press and Publications Administration of China. It attracted the support of other liberal CCP members, such as Xi Zhongxun, the father of Xi Jinping, and for many years its chief editor was the famous Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng.

The journal had upwards of 200,000 readers a month. In 2016 its reform-oriented management was dismissed as part of a crackdown on alternative histories.

The China Unofficial Archives has a complete set of <i>Yanhuang Chunqiu</i> in its database. Over time, we will index the individual issues and hope to provide English summaries.

Book

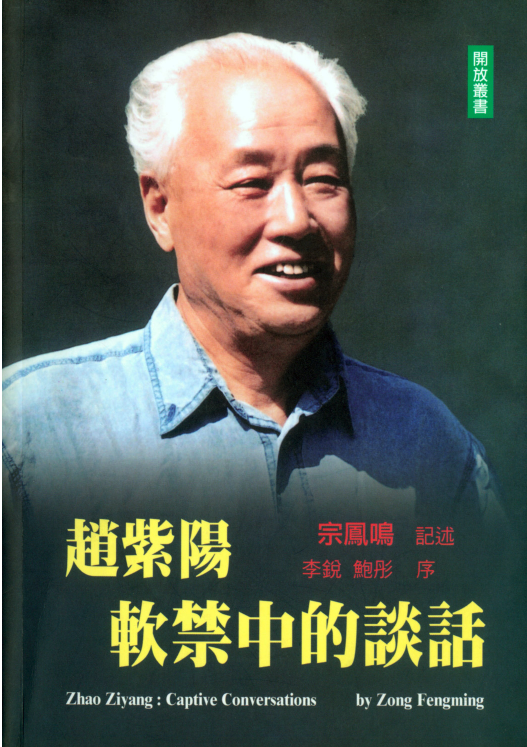

Zhao Ziyang’s Conversations Under House Arrest

In January 2007, Hong Kong Open Press published the book "Conversations of Zhao Ziyang under House Arrest". It was narrated by Zong Fengming and prefaced by Li Rui and Bao Tong. The narrator, Zong Fengming, is an old comrade of Zhao Ziyang. He retired from Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics in 1990. From July 10, 1991 to October 24, 2004, using the name of a qigong master, Zong Fengming visited Fuqiang, who was under house arrest in Beijing. Zhao Ziyang, who lives at No. 6 Hutong, had hundreds of confidential conversations with Zhao Ziyang. This book is a rich account of these intimate conversations. Zhao Ziyang talked about the power struggle and policy differences within the top leadership of the CCP, his relationship with Hu Yaobang, his evaluation of Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, his criticism of Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, Sino-US relations, the Soviet Union issue and Taiwan issues. He also conducted in-depth reflections on the history of the Communist Party.

Film and Video

Beijing's Petition Village

In China, individuals can complain to higher authorities about corrupt government processes or officials through the petition system. The form of extrajudicial action, also known as "Letters and Visits" (from the Chinese xinfang and shangfang), dates back to the imperial era. If people believe that a judicial case was concluded not in accordance with law or that local government officials illegally violated his rights, they can bring it to authorities in a more elevated level of government for hearing, re-decide it and punish the lower level authorities. Every level and office in the Chinese government has a bureau of “Letters and Visits.” What sets China’s petitioning system apart is that it is a formal procedure—and as Zhao Liang's documentary shows, the system is largely a failure.

A residential area near Beijing South Railway Station was once home to tens of thousands of residents from all over the country. Known as “Petition Village,” its bungalows and shacks were demolished by authorities several times, but many petitioners still clung to the land in search of a clear future. _Beijing Petition Village_ portrays the village in the midst of this upheaval, focusing on the thousands of civilians who travel from the provinces to lodge their complaints in person with the highest petitioning body, the State Bureau of Letters and Visits Calls in the province, only to repeatedly get the brush-off by state officials. Ultimately, in 2007, Petition Village was demolished for good.

The film went on to win the Halekulani Golden Orchid Award for Best Documentary Film at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival, and a Humanitarian Award for Documentaries at the 34th Hong Kong Film Awards.