Explore the collection

Showing 132 items in the collection

132 items

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 51): Hu Shigen

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 53): Liang Xiaoyan

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working Toward a Civil Society (Episode 54): Pu Zhiqiang

How can China build a true civil society? Independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants since 2010.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 55): Zheng Baohe

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 6): He Fang

How can China build a real civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple sat for a series of interviews with scholars and civil society actors.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 7): Guo Yuhua

How can China build a real civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple sat for a series of interviews with scholars and civil society actors.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 8): Xu Youyu

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

Film and Video

Working toward a Civil Society (Episode 9): Zhang Hui

How can China build a true civil society? Since 2010, independent director Tiger Temple has conducted a series of interviews with scholars and civil society participants.

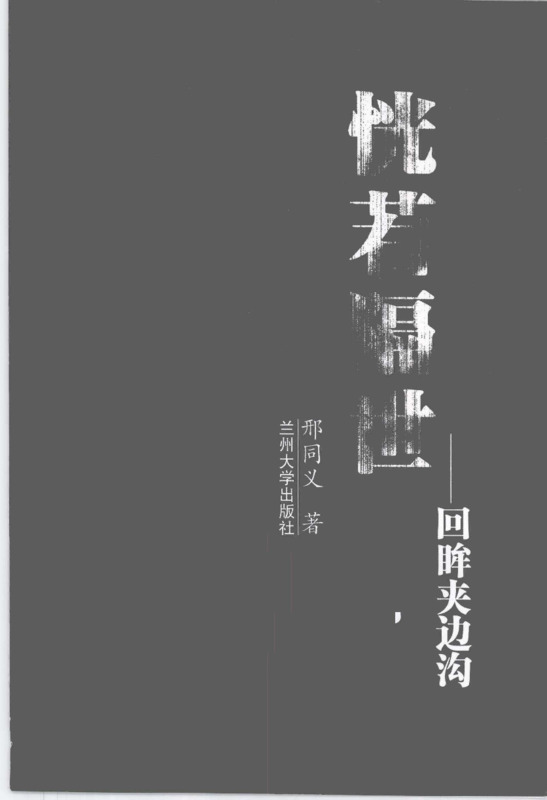

Book

Worlds Away: A Look Back at Jiabiangou

This book was published by Lanzhou University Press in 2004. The author, Xing Tongyi, once served as deputy director of Gansu People's Broadcasting Station and director of the Standing Committee of the Jiuquan Municipal People's Congress.

Jiabiangou Farm is a farm located on the edge of the Badain Jaran Desert in Jiuquan, Gansu Province, about 30 kilometers northeast of Jiuquan City. It became a labor camp in 1957. Before it was banned in October 1961, more than 3,000 intellectuals who were labeled as rightists were detained here. During the Great Famine, most of the intellectuals in farm labor camps died due to starvation and excessive workload. This is known as the Jiabiangou Incident. Jiabiangou has also become a symbol of the concentration camps where persecuted intellectuals were imprisoned.

Xing Tongyi was born in Tianshui, Gansu. He said that when he was young, he witnessed a neighbor named Guo being beaten as a rightist and sent to Jiabiangou Labor Camp. In 1961, he learned that this neighbor had starved to death in Jiabiangou. When he was in school at No. 1 Middle School in Tianshui City, his math teacher was Li Jinghang, a Christian who survived Jiabiangou. Xing Tongyi later served as a reporter and deputy director of Gansu Radio Station for a long time, and went to work in Jiuquan in 1996. After that, he took advantage of various opportunities to go deep into Jiabiangou and some surrounding labor reform farms. By consulting a large number of historical materials, he interviewed dozens of rightists who had undergone labor reform in Jiabiangou, or the children of these rightists. It took eight years to complete this book.

Unlike Yang Xianhui's novelistic description of Jiabiangou, Xing Tongyi's narrative is composed of interviews with the people involved and quotations from first-hand historical materials. According to Xing Tongyi, the historical materials he referred to include the Jiabiangou Farm's "Plan and Mission Statement" and the anti-rightist report of "Gansu Daily" in 1957. In addition to interviewing Jiabiangou survivors or their children, he also found information on more than 40 of the more than 2,000 rightists who were in labor camps at the time and were prosecuted by the Jiuquan County Procuratorate for resisting labor camps. After the book was published, people continued to provide him with historical materials, such as death notices and diaries of the victims.

How many labor camp inmates were there in Jiabiangou at that time? In order to clarify this issue, Xing Tongyi interviewed dozens of people, reviewed information, and also found Luo Zengfu, the production section chief of Jiabiangou Labor Camp, the only farm management cadre alive at the time. Based on the information provided by Luo Zengfu, Xing Tongyi's research concluded that there were a total of about 2,800 inmates in Jiabiangou Farm at that time, including about 2,500 rightists. This number is considered to be relatively accurate.

Film and Video

Xu Zhiyong

Chinese human rights activist Dr. Xu Zhiyong, twice imprisoned for his longstanding advocacy of civil society in China, was sentenced to 14 years in prison by the Chinese government in April 2023. The documentary by independent director Lao Hu Miao was filmed over a four-year period, beginning with the seizure of the Public League Legal Research Center, which Xu Zhiyong helped found in 2009, and ending with Xu's first prison sentence in 2014.

Film and Video

Beijing's Petition Village

In China, individuals can complain to higher authorities about corrupt government processes or officials through the petition system. The form of extrajudicial action, also known as "Letters and Visits" (from the Chinese xinfang and shangfang), dates back to the imperial era. If people believe that a judicial case was concluded not in accordance with law or that local government officials illegally violated his rights, they can bring it to authorities in a more elevated level of government for hearing, re-decide it and punish the lower level authorities. Every level and office in the Chinese government has a bureau of “Letters and Visits.” What sets China’s petitioning system apart is that it is a formal procedure—and as Zhao Liang's documentary shows, the system is largely a failure.

A residential area near Beijing South Railway Station was once home to tens of thousands of residents from all over the country. Known as “Petition Village,” its bungalows and shacks were demolished by authorities several times, but many petitioners still clung to the land in search of a clear future. _Beijing Petition Village_ portrays the village in the midst of this upheaval, focusing on the thousands of civilians who travel from the provinces to lodge their complaints in person with the highest petitioning body, the State Bureau of Letters and Visits Calls in the province, only to repeatedly get the brush-off by state officials. Ultimately, in 2007, Petition Village was demolished for good.

The film went on to win the Halekulani Golden Orchid Award for Best Documentary Film at the 29th Hawaii International Film Festival, and a Humanitarian Award for Documentaries at the 34th Hong Kong Film Awards.