Explore the collection

Showing 139 items in the collection

139 items

Article

The Vagina Monologues' Journey in Mainland China

This article comprehensively documents the journey of the play <i>The Vagina Monologues</i> in Mainland China, including its many performances nationwide, as well as screenings of the play and events based on the play.

The author, Rong Weiyi, is an associate professor at the People’s Public Security University of China and an expert in gender studies, serving as a member of the China Women’s Studies Association, a member of the China Marriage and Family Studies Association, and a special researcher for the China Police Association.

Film and Video

A Citizen Survey

In August 2008, after the 100-day anniversary of the Sichuan earthquake, rescue teams began to withdraw and the media stopped reporting on the casualties of school employees, teachers, and students. Chengdu environmental worker Tan Zuoren and local volunteers, however, were still searching for the cause of the collapse of school buildings within the ruins. As winter arrived, Tan Zuoren and his colleague Xie Yihui trekked through more than 80 towns and villages in 10 counties and cities, covering a total of 3,000 kilometers. Finally, before the May 12 anniversary, they issued a report of their investigation, which was the first independent inquiry report on the Sichuan earthquake’s impact on schools. At the same time, Beijing artist Ai Weiwei furthered civilian investigation and new volunteers arrived in Sichuan to search for the names of students who died. This documentary is an incomplete record of a civilian investigation and a piece of testimony submitted to the court charging Tan Zuoren with “suspected subversion of the state.”

This film is in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Film and Video

By the Sea

The family of Jia Qingyun, a farmer whose ancestors came to Guandong Province, returned to their hometown of Shandong Province with their three children due to the difficulties of life in the Northeast, and settled on the seaside of the town. However, facing the land where their ancestors had lived, they did not have land of their own. Nor did they have a household registration or a house. They can only face the sea and tenaciously start life again. Director Hu Jie records their hardships and their hopes for life.

Film and Video

Care and Love

This film records the story of Liu Xianhong, a woman from rural Xingtai, Hebei, who contracted AIDS through a blood transfusion in the hospital and decided to publicly disclose her identity and sue the hospital. After fighting in the courts, she finally received compensation. This documentary demonstrates the surging awareness of civil rights in rural China at the grassroot level through depicting the experiences of several families and the concerted efforts of patients to form “care” groups to collectively defend their civil rights. Due to public awareness, media intervention, and legal aid, the government also introduced new policies to improve the situations of patients and their families.

This film is in Chinese with both English and Chinese subtitles.

Film and Video

Chronicle of Western Liaoning, A

In 1959, in the desolate Lingyuan area in the western part of Liaoning Province, a group of intellectual rightists from the Shenyang University arrived. There, they were to labor and be reformed alongside criminal prisoners in the prison, while digging mines to build railroads. How did the Communist Party reform the intellectuals? What kind of encounters did these rightist intellectuals go through? Hu Jie's camera restores this history.

Film and Video

Cultural Revolution Propaganda Posters

Through a large number of Cultural Revolution paintings, this film shows the official aesthetics at the time of the Cultural Revolution and the bloody violence and authoritarianism behind these paintings. The film features interviews with painters and Red Guards of the era as well as collectors and researchers in China and the UK today.

Film and Video

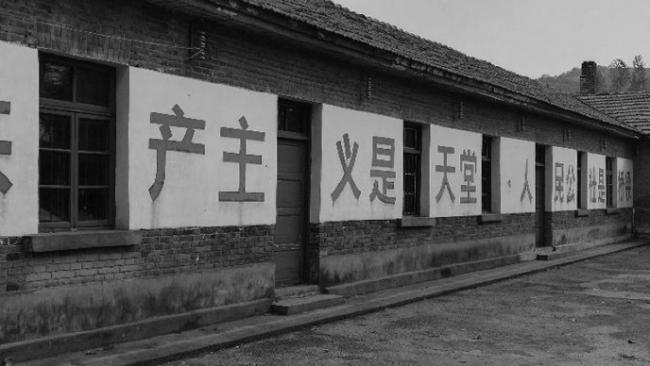

East Wind State Farm

In 1957, two hundred teachers, students, and cadres from Kunming, Yunnan were among the hundreds of thousands of Chinese people labeled as “Rightists” for criticizing the Chinese Communist Party. They were sent to the East Wind State Farm, located in Mi-le County in Yunnan, for 21 years of “thought reform” in the countryside. These inmates witnessed the policies of the Great Leap Forward first-hand: they took part in deforestation, agricultural, and industrial projects in the countryside, which precipitated the Great Famine. Later, during the Cultural Revolution, their camp was visited by large groups of youths “sent down” from the cities, who worked on the farm with the “Rightists.” In 1978, these “Rightists” were finally rehabilitated and allowed to leave.

This documentary examines the policies and campaigns of the Maoist era through the eyes of those who were persecuted and exiled. Director Hu Jie pieces together this long and complex story through collecting dozens of extensive interviews with inmates as well as staff who served through decades of the camp’s existence. These people’s vivid memories and personal accounts shed light on the harrowing lifestyle of not only the two hundred “Rightists” of East Wind State Farm, but also the scores of dissidents and youths who experienced the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Film and Video

Enemy of the State

On February 9, 2010, Tan Zuoren was tried in the Chengdu Intermediate People’s Court for the crime of inciting subversion against the state. Ai Xiaoming and her team recorded the three days before and after the verdict, the mindsets of Tan Zuoren’s friends and relatives, and how the lawyers carried out their work.

This film is in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Article

Facts of the 1958-1962 Disaster in Fengyang County, Anhui Province

The author of this book, Luo Pinghan, is a native of Anhua County, Hunan Province. He graduated from the Party History Department of Renmin University of China and served as director and professor of the Party History Teaching and Research Department of the Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China. This book was published by Fujian People's Publishing House in 2003.

With Mao Zedong's affirmation, the system of people's communes was rapidly promoted across the country in 1958. At that time, the people's commune was both a production organization and a grassroots political power. Its rise and fanatical development are closely related to the subsequent Great Famine.

As a scholar within the system, the author’s view of history also belongs to orthodox ideology. Although this book is narrated from the official ideology of the CCP, it uses rich and detailed historical materials to comprehensively and systematically introduce the history of the People's Communes, giving it a reference value for a comprehensive understanding of this movement.

Article

Famine and County (8) Huanjiang County, Guangxi: Frenzy and Its Disasters

Huanjiang County is a county in northwest Guangxi and home to multiple ethnic groups. The area is a major grain-producing county with abundant resources. In 1958, local officials followed the frenzy of the Great Leap Forward, and engaged in "satellite launches"--giving astronomically high grain production rates. This formed the basis of taxation policies, which stripped localities of grain and was a key reason for the famine. Huanjiang County exaggerated grain production up to three times the actual production.

In order to complete the high procurement, the county merged all the people's rations and feed grains for pigs, cattle and livestock into the national warehouse, and implemented the policy of not opening the warehouse for relief even if people died of starvation. As a result, widespread famine occurred in the county. Huanjiang County has a population of about 150,000, and about 50,000 farmers starved to death.

This article uses specific figures and historical details to fully describe how the regime created false grain figures step by step, and how the upper-level leaders encouraged such a trend. From it we can see the specific process of the Great Leap Forward policy.

Article

Famine and Village: Who Starved Them to Death?

The author of this article, Chen Feng, was born in 1962. His hometown is Huang Sichong, Sanjia Brigade, Bainong Commune, Feidong County, Anhui Province. According to his records, in the winter of 1959 to the spring of 1960 during the Great Famine, his grandfather, grandmother, grandfather, grandmother's relatives and relatives, and countless members of his extended family and village, 57 people died of starvation.

Article

Famine in one County: Zhenyuan's Wrongful Case during the Great Leap Forward

The population in Zhenyuan County in Gansu was starving to death as early as 1957. However, the authorities believed that the food problem was due to "counter-revolutionaries" and created a huge case of injustice in which at least 1,650 people in the county were implicated. This article was published by the Zhenyuan Party History Office of the Communist Party of China (CPC) in *Hundred year tide* magazine. This article is reprinted from the "Famine Archives" website.

Film and Video

Faraway Mountain

This movie captures the lives of miners in small coal mines in the Qilian Mountain area of Qinghai Province. At 3600 meters above sea level, the air here is thin. Miners in the small coal kilns labor hard in a working environment without any protection, and usually get silicosis after 5-10 years of work, thus losing their ability to work. If they die in an accident, their families receive only meager compensation. This is a true record of the survival of China's grassroots laborers in the early 1990s.

Film and Video

Fiber City

Fiber City—the collective name Fujian Textile and Chemical Fiber Factory—was founded in 1971. China's first production in the 1970s, one of the nine Vinylon factories located in Yongan City, Fujian Province, deep in the mountains, 3 kilometers outside the outskirts of the industrial town. Once glorious, it has been gradually lowering its curtains. The old factory buildings are mottled, its young workers are now gray-haired, and many have left. The documentary shows the fate of this big factory during the planned economy.

Film and Video

Garden of Paradise

The year 2003 was known as the birth of the Weiquan—the rights defense–movement, which was marked by the Sun Zhigang incident in Guangzhou. At the same time, a campaign began to get justice for Huang Jing, a teacher from Hunan who was sexually assaulted and killed by her boyfriend. The campaign involved the victim’s family, netizens, feminist scholars and activists, and lasted for several years. This documentary records the process of Huang Jing’s case from filing to post-judgement, and analyzes the broader issue of sexual violence against women in China.

The films in this series are in Chinese with Chinese subtitles.

Article

Historical Examination of the Purge of the "AB" Regiment

More than 70 years ago, a massive wave of revolutionary terror swept through the CCP-led Jiangxi Soviet Union. Thousands of Red Army officers and soldiers, as well as members of the Party and the general public in the base area, were brutally murdered in a purge called the "Purging of the AB Troupe." Gao Hua's article examines why Mao Zedong initiated the "purge of the AB Group" in the Red Army and the base areas. What was Mao's rationale for the Great Purge? What is the relationship between the Great Terror and the establishment of a new society? Why did Mao stop using the "Fighting the AB Groups" as a means of resolving internal conflicts in the Party after he assumed real power in the CCP?

Article

Huang Sha, 2019 National Survey on the Treatment of Detainees in Custodial Facilities

This report focuses on the human rights situation in detention centers in China. Mr. Huang Sha distributed the questionnaire to the practicing lawyers he knew, and then the practicing lawyers took the questionnaire and filled it out in the form of questions and answers when they met detainees in the detention centers. The questionnaires were then collected and counted, resulting in a research report. The span of time for filling out the questionnaire in the detention center is: from July 2, 2019 to November 19, 2019. There were 101 valid questionnaires recovered.

电影及视频

In Search of Lin Zhao's Soul

Hu Jie narrates the life of Lin Zhao, a Christian dissident who was condemned as a Rightist in the late 1950s and executed during the Cultural Revolution. Prior to becoming a mentcritic of the government, Lin Zhao was an ardent believer of communism. She demonstrated talent in writing and speaking as a star student in Peking University. However, after criticizing the government in 1957 during the Hundred Flowers Campaign, she was cast as anti-revolutionary. Despite the government’s attempts to silence her, Lin Zhao continued to speak and write publicly, including contributing two epic poems to Spark, an underground student-run journal. In 1960, she was arrested, and despite being released briefly in 1962, spent the rest of her life behind bars, under extremely poor living conditions. Nevertheless, she continued to write in prison, sometimes with her blood. In 1968, at the age of 36, she was executed by a firing squad.

In this documentary, Hu Jie showcases many of Lin Zhao’s surviving writings and poetry. These pieces often contain criticisms of the communist regime, as well as commentary on policy issues pertaining to labor and land reform. In making this film, Hu Jie traveled around China to interview friends and associates of Lin Zhao, who knew her as a student, activist, or prisoner. This documentary includes excerpts from interviews with them, which inform us about Lin Zhao’s personality and motivations.

This documentary has contributed to a widespread revival of interest in Lin Zhao, who had almost become a forgotten figure until the film’s appearance.

Film and Video

Jiabiangou Elegy: Life and Death of the Rightists

A five-part documentary by the filmmaker and feminist scholar Ai Xiaoming on the persecution of inmates at the Jiabiangou labor camp in Jiuquan, Gansu province, where more than 2,000 people died. The movie includes interviews with the few remaining survivors and documents efforts to commemorate the dead. The director interviewed survivors of Jiabiangou and the children of the victims and listened to their stories about the past; she also found former correctional officers and their descendants to understand the causes of labor camps and the Great Famine from different angles.

Shot by Ai and a team of volunteers, the film presents the conflict between the preservation and destruction of memory.