Explore the collection

Showing 32 items in the collection

32 items

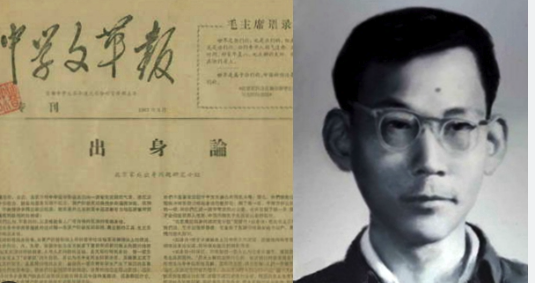

Article

On Family Background

Yu Luoke (May 1, 1942 - March 5, 1970): Worker, freelance writer, and public intellectual.

Yu was born into an educated family in northeastern China, which for a period of time was under Japanese occupation. His father studied on a state scholarship in Waseda University in Tokyo, while his mother came from a wealthy family in Beijing and studied business at Tokyo Girls High School. When the two returned to China, they went into business, married, and had three children.

When the CCP took power, the family was declared part of the “bourgeois class” and like other “black elements”--classes of people who the party declared to be enemies–was persecuted. The father was arrested in 1952 on charges of tax evasion and released. In 1957, Yu Luoke’s parents were declared Rightists and sent to labor camps. In 1959, Yu graduated from high school with highest honors but as the offspring of an undesirable class was not permitted to attend university. In 1961, he was allowed to work on a farm in a Beijing suburb, where he realized that class identity was also important in rural China–landlords and their children were even beaten to death. In 1964 he returned to the city and apprenticed at a machinery factory. Yu realized that he was part of an untouchable caste in Maoist China and would be condemned forever, no matter what he believed or how hard he worked.

These experiences were the genesis of Yu’s essay, which became one of the most famous texts of the Mao era. Yu wrote it at the start of the Cultural Revolution. The ten-thousand character essay is called chushenglun, or “On Family Background” (sometimes translated as “On Class Origins"). In it, he warned that the “five black categories'' were becoming a permanent underclass, while China’s rulers were from the hongwulei, or “five red categories:” poor and lower-middle peasants, workers, revolutionary soldiers, revolutionary officials, and revolutionary martyrs, including their family members, children, and grandchildren. He warned of a new ruling class based on bloodlines.

The essay was published in a journal that Yu and his brother Yu Luowen called the "Journal of Secondary School Cultural Revolution." In January 1967, about thirty thousand copies were printed, and the young men began distributing them around the capital, selling them for two cents a copy. They sold out in a few hours. In February, they printed another eighty thousand copies.

Soon, hundreds of letters each day arrived at Yu Luoke’s local post office—so many that he had to go collect them in person. The missives detailed how the Communists’ policies had caused them to suffer. People traveled from across China to visit them at their home, excited that someone finally had uncovered how the Chinese Communist Party ruled. The editorial board was expanded to twenty people, and the group sponsored debates and seminars.

The Journal was closed down in April 1967. Yu Luoke began to write on economic inequality. In January 1968, he was arrested. Two years later, on 5 March 1970, Yu was executed by firing squad at Beijing Workers Stadium.

Book

Personal experiences of political movements

This book is a collection of many authors, most of whom were former senior officials of the Communist Party of China, such as Li Rui, Xiao Ke and others. Through the author's recollections, we can learn about the political movements of the Mao Zedong era, including the Cultural Revolution, the Anti-Rightist Movement, etc., as well as the details of many unjust cases, such as the Hu Feng case, which is quite convincing. This book was published by the Central Compilation and Translation Bureau Press in mainland China in 1998.

Book

Revisiting 1957

<i>Revisiting 1957</i> is not just about the history of the Anti-Rightist Campaign but is also a theoretical reflection on that history. Written by Wei Zidan (the penname for Wei Liyan), the book has three sections: upper, in which the author discusses philosophical problems of the campaign; middle, in which he discusses the origins of the campaign; and lower, which contains his thoughts on lessons for the future. In Wei's view, the people who were declared rightists stood up for freedom of speech. The campaign, therefore, was an assault on freedom of expression and resulted in a human rights catastrophe for China. The book also has an eleven-part appendix with reflections on miscellaneous events.

Wei Zidan was born in Henan Province in 1933 and was a teacher in the Anyang Middle School. He himself was labeled a rightist and brings a unique insider's account of the movement but unlike some personal accounts of suffering, Wei also brings a more analytical approach to the issue.

After moving to the United States in his later years, he collected information and found the freedom to complete this book. Published in Hong Kong in 2013 by the May 7 Society Press.

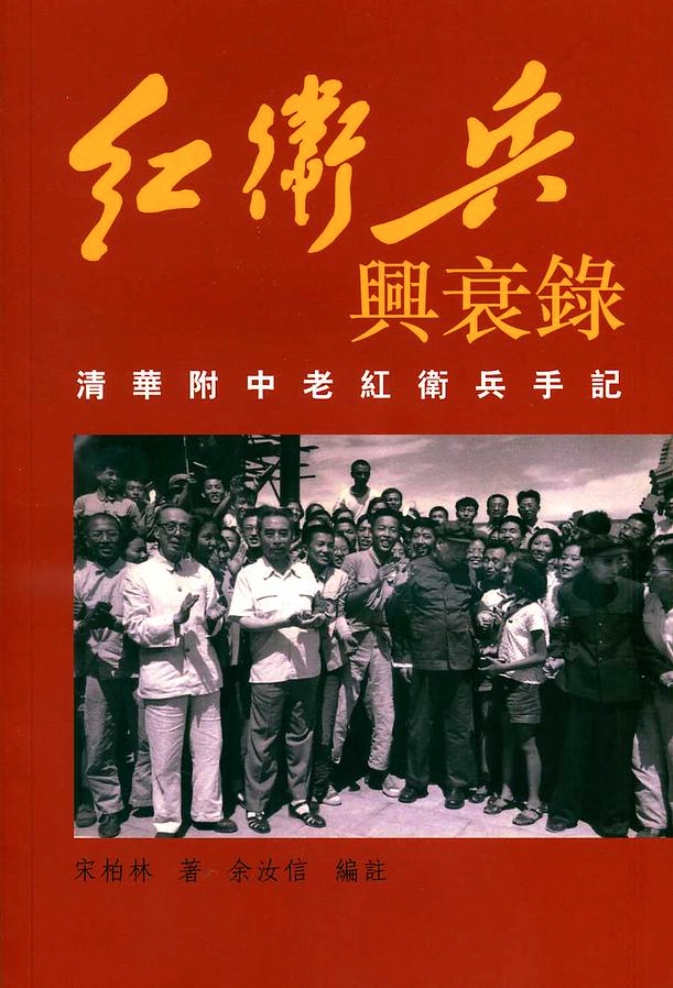

Book

Rise and Fall of the Red Guards: A Handbook of the Old Red Guards at Tsinghua High School

The Red Guard movement originated in the Tsinghua University Affiliated High School, a secondary school for faculty and staff of the university, as well as others aspiring to attend the elite university, including the sons and daughters of high-ranking cadres. Song Bailin was a senior high school student at Tsinghua High School, one of the founders and a core member of the Red Guards.

Song kept a diary during the first years of the Cultural Revolution. Yu Ruxin, a researcher of the Cultural Revolution, felt that a section of Song Berlin's diary involving the Red Guards of Tsinghua High School was of historical value. Yu decided to publish the diary in its entirety as it was, with no deletion except for the correction of obvious typos. The diary covers the period from May 1966 to February 1968, the launching phase of the Cultural Revolution. A selection of diary entries from January to April 1966 has been included to give a better understanding of the political climate in China on the eve of the Cultural Revolution as well as the ideological trends of high school students.

Because the diary is a historic document directly from an era that is now more than half a century old, the diary lacks historical background and footnotes that might help current readers understand the context of that time. Fortunately, the current publication has a preface written by Luo Xiaohai, who explains the political atmosphere in the years leading up to the Cultural Revolution and some of the key events of that time.

For readers today, the diaries are at times hard to decipher. The Red Guards quickly were criticized by others, including those in power. As the writer Hu Ping notes <a href="https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/pinglun/huping/Hu_ping-20071112.html">in a 2007 review of the book</a>, the reversal of support for the Red Guards must have caused confusion and even a sense of betrayal by many involved. The diary, however, reveals none of this inner turmoil, Hu Ping ascribes the Red Guards' silence to the fact that keeping a diary in that era was a way for participants to prove their revolutionary zeal. Thus they self-censored and wrote with the expectation that their words would be discovered and could be used against them. This means the diary provides little in the way of psychological insights in the Red Guards.

It does, however, provide a way of understanding how totalitarian terror and power works on individual psychology. Thus when his classmates beat classmates and teachers, Song expressed embarrassment that he lacked their fervor and did not participate. This means that the diary is best seen as a primary document that shows the way young people thought at that time, rather than an exercise in self-reflection or criticism.

Book

Seventy Years of the Chinese Communist Revolution

Professor Chen Yongfa's book examines the history of the Chinese Communist Party from the perspective of modern Chinese history. It divides it into three stages: revolutionary seizure of power, continuous revolution, and farewell revolution. It delves into three major issues in CCP history: nationalism, grassroots power structure, and ideological transformation and control. published by Taiwan's Linking Publishing in 2001.

Book

Ten Years of War: A Memoir of Sino-Soviet Relations 1956-1966

The author of this book explains the relations between the two parties before and after the 1956-1966 Sino-Soviet War and the main process of the Sino-Soviet War as a first-hand witness. Since Stalin's death and Khrushchev's rise to power, Sino-Soviet relations have been characterized by a series of exchanges over the internal relations between the socialist party and the socialist country, the relations with the "imperialists", how to build socialism, and the national question. As a personal witness to this period, the author tells the truth about history as he knows it. This book was originally published on the mainland in 1993.

Book

The Doubtful Clouds of 1957-- Cracking the Code of the Anti-Rightist Movement

The Anti-Rightist Movement in China began in 1957 with the reorganization of intellectuals, followed by the Great Leap Forward, the People's Commune, and a series of calamities such as the Great Famine. The Hong Kong Five Sevens Society was founded in 2007 with the aim of collecting, organizing, and researching historical information about the Anti-Rightist Movement. It is headed by Wu Yisan, a writer who moved to Hong Kong from mainland China. The author of this book, Shen Yuan, who was also a Rightist at the time. He has systematically researched and organized the Anti-Rightist Movement that took place in 1957 and attempted to answer some of the unanswered questions.

Book

The Great Leap Forward: An Intimate Memoir

Li Rui, who once served as Mao's secretary, is also an expert on Mao Zedong. Like his famous <i>Proceedings of the Lushan Conference</i>, this book is also an important historical work. It focuses on the author's personal experience of the Great Leap Forward initiated by Mao Zedong.

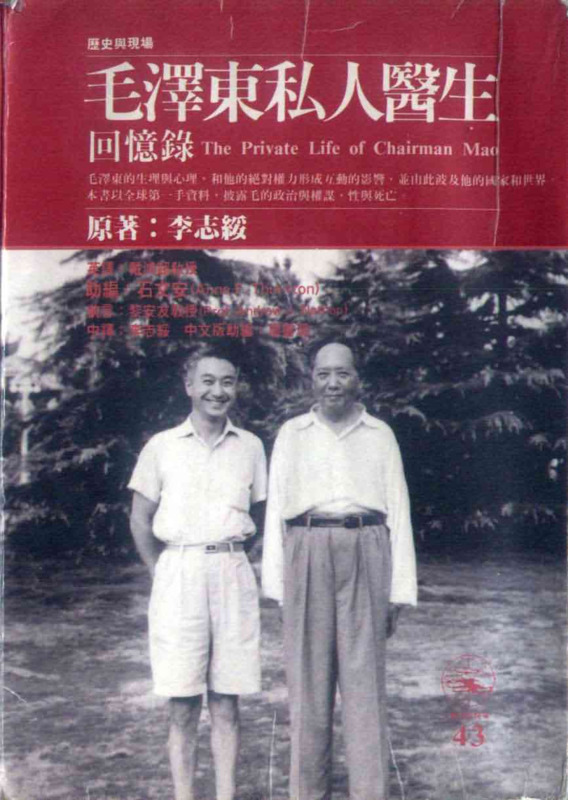

Book

The Private Life of Chairman Mao

Author Li Zhisui served as Mao's medical team leader and was the first director of the PLA's San 105 Hospital. This book is a memoir that he wrote. It details Li Zhisui's information from 1954, when he started as Mao's personal physician, to 1976, when Mao died, a period of 22 years. In his writing, Mao's private life is extremely absurd and touches on all aspects of the struggle against some of the CCP's personnel. After the book was published in Taiwan, it was completely banned on the mainland.

Originally written in English, the book was translated into English by Hongchao Dai, former head of the political science department at the University of Detroit, with a foreword by China expert Andrew James Nathan, and with Anne F. Thurston as an assistant editor. was published in English by Blue Lantern Books in 1994. The Chinese edition was translated from the English with the assistance of Shushan Liao and published by Taiwan Times Culture in 1994. Lee died in the United States in February 1995, six months after the book was published.

Book

Thirty Years of New China

Tang Degang is a historian and biographer who specializes in oral history. In the latter half of his life, he settled in the United States and taught at Columbia University and the City University of New York. In the field of history, he put forward the "Three Gorges Theory of History", which divides the change of Chinese social system into three major stages: feudalism, imperialism, and civil rule. The book was originally titled <i>Mao Zedong's Dictatorship, 1949~1976</i>, but was renamed <i>Thirty Years of New China </i> when it was released on the mainland.

Book

Who is the New China

Author Xin Hao Nian tries to analyze the modern history of China since the Xinhai Revolution. He pointsout that the People's Republic of China (PRC) is a restoration of the authoritarian system, and the Republic of China (ROC) represents China's road to a republic. The first volume of the book defends and clarifies the history of the Kuomintang (KMT), arguing that the KMT is not a "reactionary faction" as claimed by the CCP. The second volume criticizes the revolution and history of the CCP. The book was first printed in 1999 by Blue Sky Publishing House (USA) and reprinted in June 2012 by Hong Kong's Schaefer International Publishing. It is banned on the mainland.