Explore the collection

Showing 58 items in the collection

58 items

Book

Chronicle of Jiabiangou

Jiabiangou was a labor reform farm in Jiuquan County, Gansu Province, where "rightist" prisoners were held. October 1957, nearly 3,000 educated people were detained there. In October 1961, when the higher-ups corrected the "left-leaning" mistakes of the Gansu Provincial Party Committee and began repatriating the rightist prisoners, less than half had survived.

Writer Yang Xianhui spent five years interviewing more than a hundred people and brought to light the truth that had been sealed for more than forty years. Originally published by Tianjin Ancient Books Publishing House in 2002, this book also includes other short and medium-sized stories by Yang Xianhui.

Book

Chronicle of Rural Remediation of Communes in Difficult Times

Two years after the Great Famine of 1958, the government sent "rectification" work teams of about 10,000 people to many of the most severely affected provinces, such as Henan, Shandong, Anhui, Guizhou, Sichuan, Qinghai, and Xinjiang. The author of this book, Hui Wen, had just graduated from Renmin University of China and was assigned to work at the Institute of Modern History of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for half a year. In December 1960, he was sent to Jianyang, Sichuan to participate in the whole society. The book records what he saw during this period. heard.

Hui Wen came into contact with a large number of farmers and witnessed the situation of rural areas on the front line. Each article in the book records the date, place and passage of writing at that time, which adds to the history and authenticity of the book. After the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, the author compiled these records into a volume. Through a case study of Jianyang, this book uses specific historical details to reflect the relationship between the Great Leap Forward policy and the Great Famine.

After the book was completed, due to China's strict publishing censorship system, the author did not submit it to a publishing organization and chose to circulate it among friends first. Later, he handed the manuscript to the website "China's Great Famine Archives," and this historical record was made public to the world.

Book

Chronicle of the Dingxi Orphanage

After the disaster in Dingxi Prefecture, which was the hardest-hit area of Gansu Province during the 1958-1960 famine, a children's welfare institution was urgently set up in Dingxi Prefecture to take in hundreds of orphans. During the same period, children's welfare centers or "kindergartens" were set up in all counties and towns in Dingxi Prefecture, as well as in the people's communes in the hardest-hit counties. These children's welfare centers, large and small, housed about 5,000 orphans. On the basis of faithful historical facts and statements by the parties concerned, this book brings tragic scenes of starvation and death before people's eyes using straightforward description, documentary language, and a down-to-earth tone of voice.

Film and Video

Chronicle of Western Liaoning, A

In 1959, in the desolate Lingyuan area in the western part of Liaoning Province, a group of intellectual rightists from the Shenyang University arrived. There, they were to labor and be reformed alongside criminal prisoners in the prison, while digging mines to build railroads. How did the Communist Party reform the intellectuals? What kind of encounters did these rightist intellectuals go through? Hu Jie's camera restores this history.

Book

Disillusionment of Splendor: A Cautionary Tale of a People's Commune

This book tells the story of China's first people's commune - the Chayashan People's Commune in the author's hometown. Chayashan is a township located in Suiping County, Xinyang City, southern Henan (now part of Zhumadian District). It is the location of the country's first people's commune established by Mao Zedong in 1958, and was also a model commune during the Great Leap Forward period. At the Lushan Conference in 1959, the commune was used in Mao Zedong's counterattack against Peng Dehuai, a general who opposed Mao's policies.

The author Kang Jian is a war veteran. More than thirty years after the Great Famine, Kang Jian visited the villages in Chayashan to conduct an oral history investigation. He used oral interviews to record the daily lives and experiences of farmers under collective economic practices. The author writes in the form of interviews, showing the history of Chayashan People's Commune in detail, and using specific cases to present the relationship between national political behavior and individual destiny.

Film and Video

East Wind State Farm

In 1957, two hundred teachers, students, and cadres from Kunming, Yunnan were among the hundreds of thousands of Chinese people labeled as “Rightists” for criticizing the Chinese Communist Party. They were sent to the East Wind State Farm, located in Mi-le County in Yunnan, for 21 years of “thought reform” in the countryside. These inmates witnessed the policies of the Great Leap Forward first-hand: they took part in deforestation, agricultural, and industrial projects in the countryside, which precipitated the Great Famine. Later, during the Cultural Revolution, their camp was visited by large groups of youths “sent down” from the cities, who worked on the farm with the “Rightists.” In 1978, these “Rightists” were finally rehabilitated and allowed to leave.

This documentary examines the policies and campaigns of the Maoist era through the eyes of those who were persecuted and exiled. Director Hu Jie pieces together this long and complex story through collecting dozens of extensive interviews with inmates as well as staff who served through decades of the camp’s existence. These people’s vivid memories and personal accounts shed light on the harrowing lifestyle of not only the two hundred “Rightists” of East Wind State Farm, but also the scores of dissidents and youths who experienced the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Book

Experience: My 1957

Born in 1932, He Fengming and her husband Wang Jingchao were both labeled "rightists" during their work at the Gansu Daily Newspaper. In late April 1958, they were sent down to work at the Anxi Farm in Jiuquan. Her husband was sent to the famed Jibiangou Farm, where he died of starvation during the famine of 1960, but she survived. In order to refuse to forget, she spent ten years writing a 400,000-dollar self-narrative, *Experience - My 1957*. The book was published by Dunhuang Literary Publishing House in 2001.

Article

Famine and Village: Who Starved Them to Death?

The author of this article, Chen Feng, was born in 1962. His hometown is Huang Sichong, Sanjia Brigade, Bainong Commune, Feidong County, Anhui Province. According to his records, in the winter of 1959 to the spring of 1960 during the Great Famine, his grandfather, grandmother, grandfather, grandmother's relatives and relatives, and countless members of his extended family and village, 57 people died of starvation.

Book

Fifty Years of the Chinese Communist Party

The author Wang Ming was an early member of the Communist Party of China (CCP) and the first of the "28 and a half Bolsheviks," who lost power after the Yan'an Rectification and were gradually marginalized by Mao. After the Yan'an Rectification, the Internationalists, led by him, lost power in the party. He was gradually ostracized by Mao Zedong, who expatriated him to the Soviet Union in 1956. In his book, Wang Ming recounts his decades-long feud with Mao. It provides a fascinating insight into the early history of the CCP.

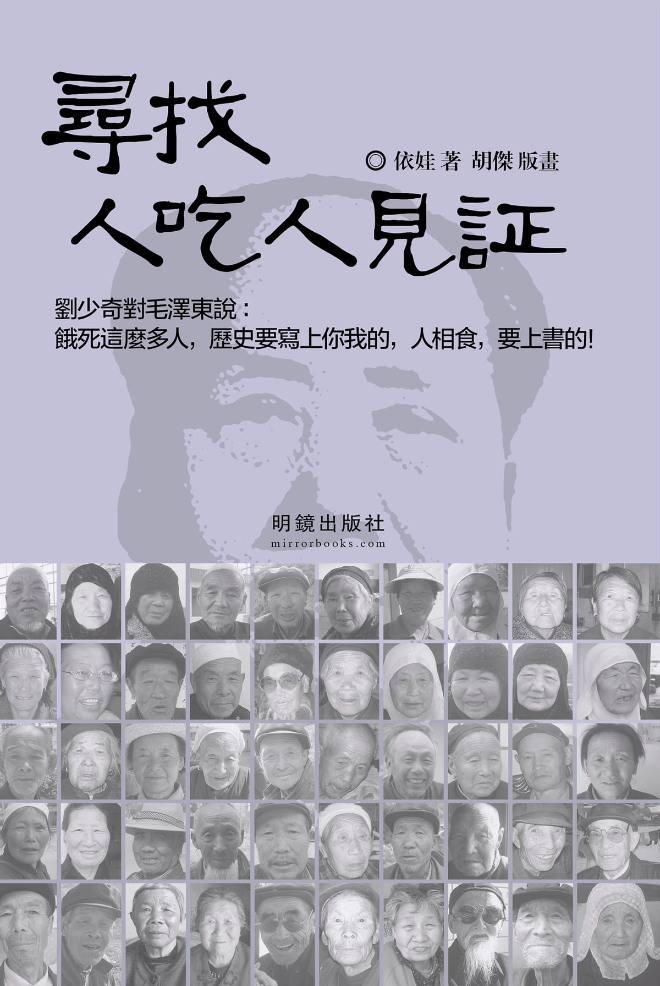

Book

In Search of Cannibal Witnesses

This book is part of author Eva's "Famine Trilogy." Because her mother was a survivor of the famine in Gansu, Eva has obsessively pursued and recorded that tragic history. She visited a dozen counties in Gansu and Shaanxi four times and interviewed two hundred and fifty people. The list of starving victims recorded in the book is about eight hundred and thirty, while as many as one hundred and twenty-one incidents of cannibalism and cannibalistic phenomena were recorded.

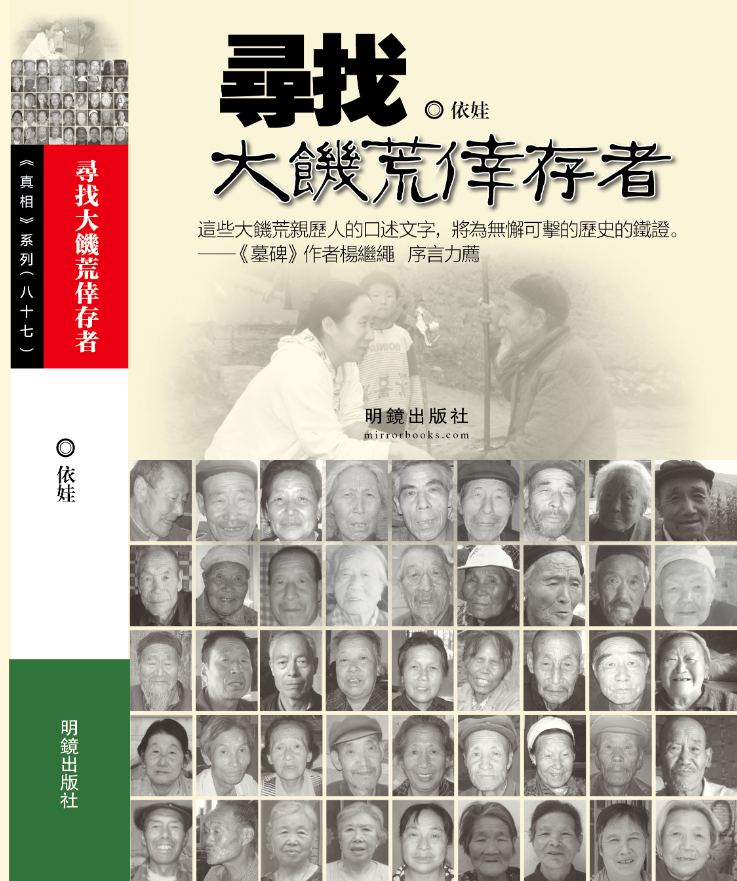

Book

In Search of Famine Survivors

This is the first book in author Eva's "Famine Trilogy," in which she traveled to Qin'an County, Tongwei County, and Tianshui District in Gansu Province as well as to Yaozhou and Tuxian County in Shaanxi Province in 2011. She interviewed more than two hundred survivors of the Great Famine, with the oldest person being ninety-five years old and the youngest being fifty-eight years old. This book allows these lowest class, mostly uneducated peasants to speak and provide their own witness, leaving behind their voices and oral history. Based on interviews with more than fifty interviewees, the book contains the names of more than five hundred victims and forty-nine incidents of cannibalism.

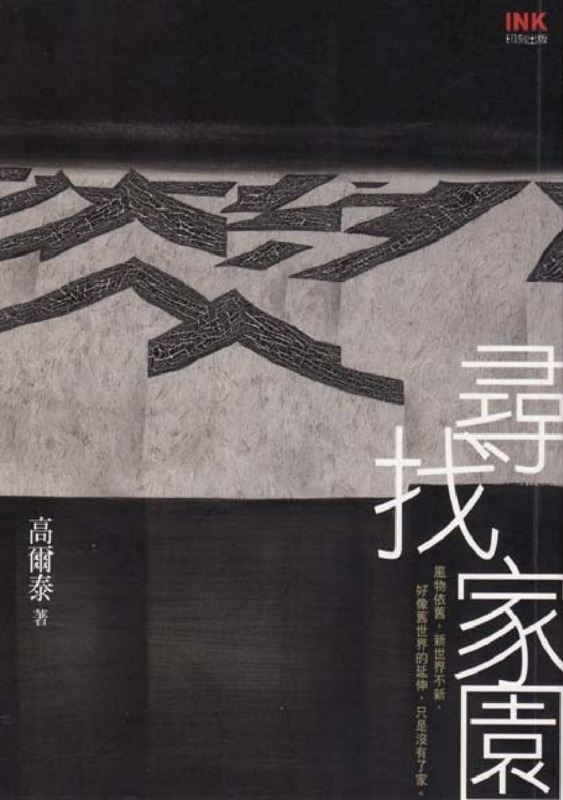

Book

In Search of My Homeland

“In Search of My Homeland” is a collection of essays in three volumes written by Gao Ertai during his exile abroad. In this book, Gao looks back on his life. From his hometown of Gaochun, a small town in Jiangsu Province, to Suzhou, then to Lanzhou, Jiuquan, Dunhuang, Beijing, Chengdu, and the United States, Gao has undergone tremendous suffering, lost his home and family, and finally had to go into exile in a foreign country. Even though the work is widely regarded as having great literary merit, Gao uses real names and places, which makes the work a valuable historical document, especially for describing the Great Famine, and the brutal suppression of intellectual life during the Cultural Revolution at the Dunhuang research academy, which is one of China's most prestigious cultural institutions.

In an [interview](https://web.archive.org/web/20240130211408/https://www.aisixiang.com/data/80804.html), Gao explained why he wrote the book: "Searching for my homeland is nothing but searching for meaning.... Life is short and small, and its meaning can only be rooted in the external world and in the long history. My sense of drift and meaninglessness, that is, a feeling that the world has no order, history has no logic, and the individual has no home, seems to be a kind of destiny. My writing is nothing but a resistance to this destiny."

In 2004, a censored version of the first two volumes of this book was published by Huacheng Publishing House in Guangzhou; in 2011, an updated version was published by Beijing October Arts and Literature Publishing House, but still censored. The version uploaded to our archive is the traditional Chinese version of the complete three volumes published by Taiwan INK Publishing House in 2009.

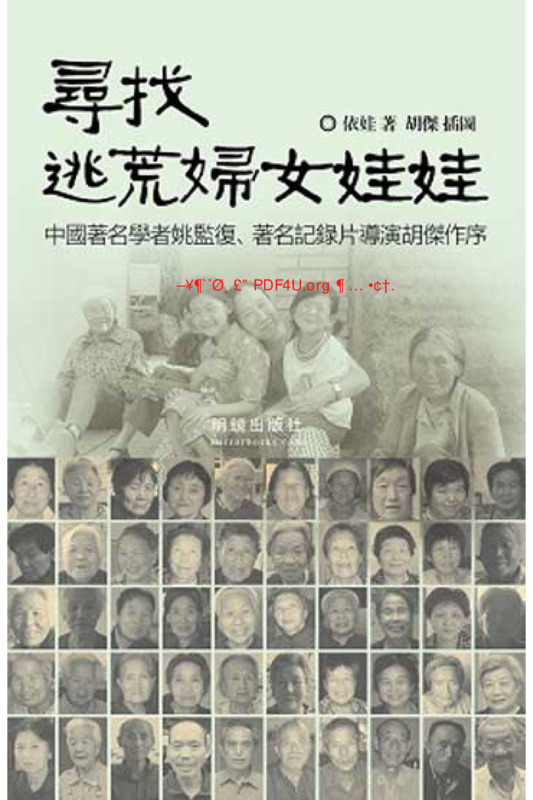

Book

In Search of the Fleeing Women and Children

This book is part of writer Eva's "Famine Trilogy." It is also the only oral history monograph on women and children who fled the famine in Gansu and Shaanxi from 1958 to 1963 as of now. More than 1.3 million people starved to death in Gansu Province, the hardest-hit area of the Great Famine, and more than 100,000 women between the ages of 16 - 15 years old fled the famine and left Gansu. What happened to them and their children is one of the most tragic memories of the Great Famine.

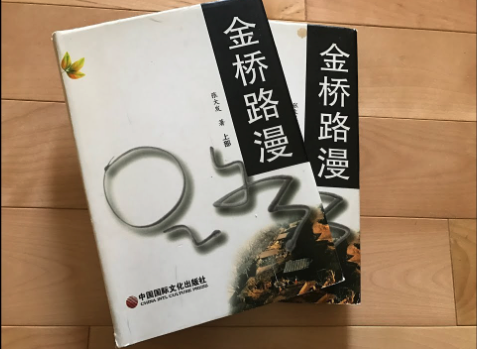

Book

Jin Qiao Lu Man

During the three years of famine from 1959 to 1961, Tongwei's unnatural deaths due to starvation and its related factors amounted to one-third of the county's population. Mr. Zhang Dafa, who worked in Tongwei for many years and later took part in the preparation of the new Tongwei County Record. Published in 2005 through the Dingxi Writers' Association, this is a collection of his many social research reports on the Tongwei issue, "Jinqiao Luwan," which profoundly reveals the tragedy and gravity of the Great Famine, a man-made disaster, within the boundaries of a single county.

Book

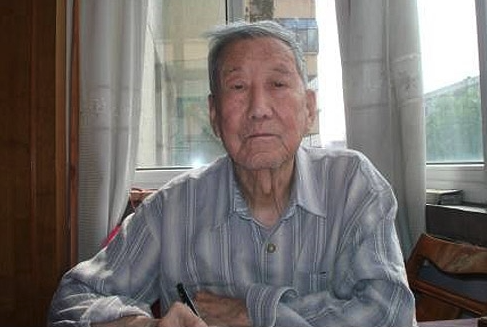

Journey of Grace, The

Li Jinghang, a native of Tianshui City, Gansu Province, 1922-2016, graduated from the Mathematics Department of the Northwest Normal College in 1949. In the fall of the same year, he was employed as a mathematics teacher at Tianshui No. 1 Middle School. In 1957, he was wrongly classified as a Rightist and sent to Jiuquan, Gansu Province to be reeducated through labor for nearly three years; in 1960, he resumed his work as a teacher at Tianshui No. 1 Middle School. In 1962, he removed his hat as a Rightist. He was rehabilitated in 1978. In 1980, he was transferred to Tianshui Teachers' College (which was upgraded to an undergraduate institution in 2000). After retiring in the fall of 1987, he joined the Church to serve full-time.

In 1957, Li Jinghang was labeled a rightist and sent to Jiabiangou for re-education through labor. In 1960, he was transferred to the Mingshuihe Farm in Gaotai, where the conditions were even worse, and he was subjected to a great deal of torture and abuse. The fourth chapter of his autobiography, "Chronicle of the bitter life in Jiabiangou," and the fifth chapter, "Chronicle of the life after returning home," are written about his bitter experience in Jiabiangou. From this, we can see the glory of humanity and the power of faith in the midst of suffering. This book was published by a Hong Kong Tianma Book Company Limited in 2003, with a print run of 2,000 copies, and reprinted once in 2004.

Book

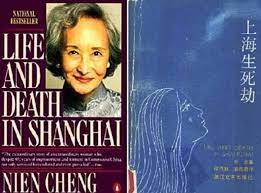

Life and Death In Shanghai

"Life and Death In Shanghai" (also known as "Shen Jiang Meng Hui") is an autobiography by female writer Zheng Nian. First published in English in 1986, it was subsequently translated into various languages and published in various countries. In the book, Zheng Nian recounts her personal experiences from the beginning of the Cultural Revolution to her departure from China in the early 1980s. After her release from prison in 1973, she learned that, shortly after her imprisonment, her only daughter, Zheng Meiping, had been persecuted and had died. She then tried to find out the cause of her daughter's death. The book traces how the ideals of intellectuals were crushed by politics.

Book

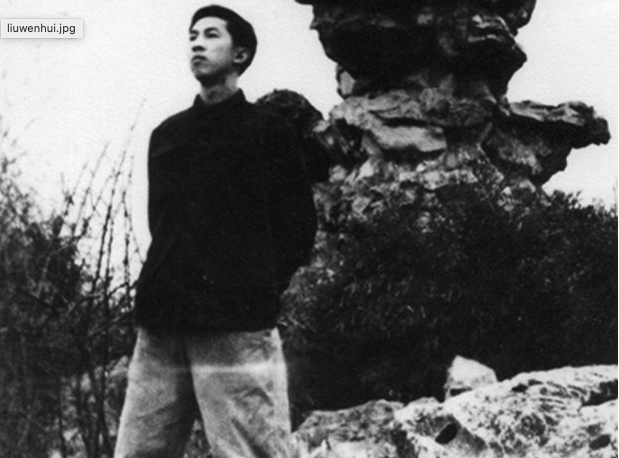

Life of Storms: The New Life of a Disabled Prisoner, A

On August 8, 1966, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China adopted the "Sixteen Articles" of the Cultural Revolution. Soon after, Liu Wenhui, a young mechanic in Shanghai who had been labeled as a Rightist in 1957, wrote pamphlets and leaflets clearly opposing the Cultural Revolution, the "Sixteen Articles," authoritarianism, and tyranny. Liu was arrested on November 26 of that year. Four months later, he was executed for "counter-revolutionary crimes." Liu Wenhui became the first person known to have been publicly shot for opposing the Cultural Revolution. The author of this book, Liu Wenzhong, was Liu Wenhui's co-defendant and survived thirteen years in prison. In this autobiography, Liu Wenzhong describes in detail not only Liu Wenhui's ideology but also how he was killed by the tyrannical government.

Book

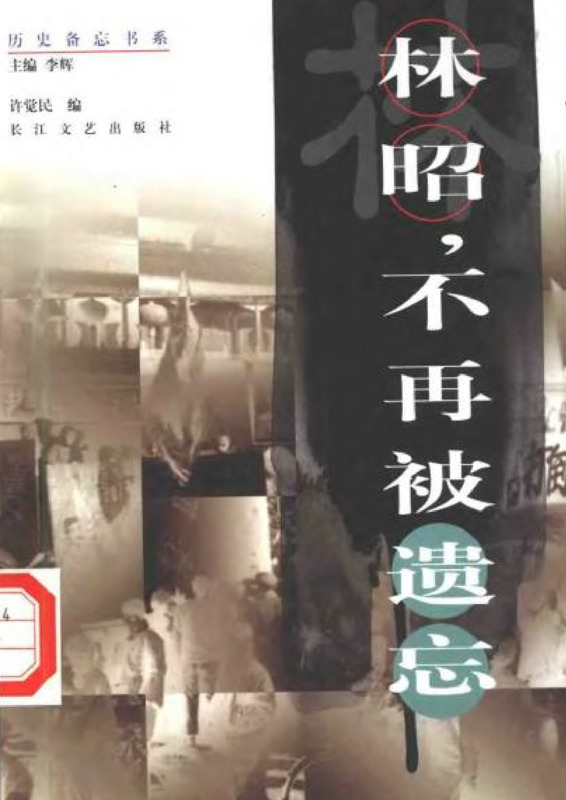

Lin Zhao: No Longer Forgotten

This book contains a number of articles in memory of Lin Zhao. It concerns the death of Lin Zhao as well as Lin Zhao's love, pursuits, and disillusionment. This book was published by Changjiang Literature and Art Publishing House in 2000.

Book

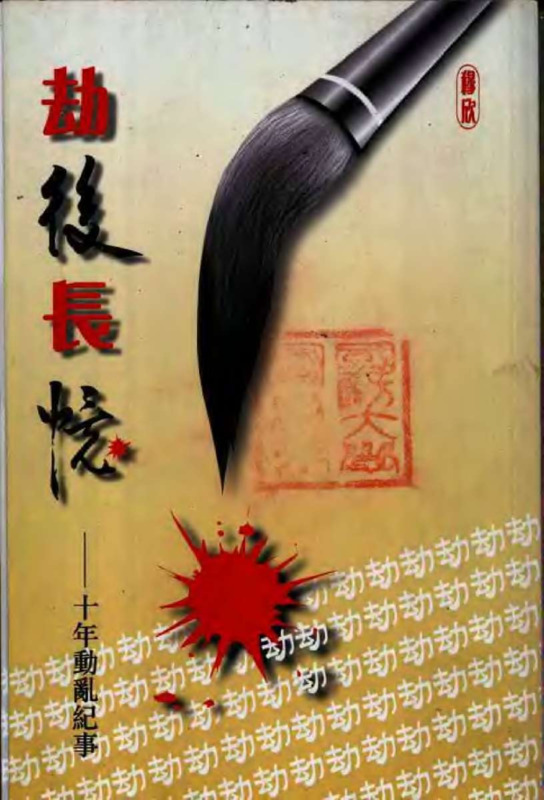

Long Memories after the Hijacking -- Chronicle of Ten Years of Turmoil

The author of this book, Mu Xin, was an early member of the CPC and served as chief editor of "Guangming Daily" in the 1950s. At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, he was a member of the Central Committee's Cultural Revolutionary Group. In 1967, he was defeated and imprisoned in the Imperial Prison (Qincheng Prison). This book was published in Hong Kong in 1997. Because of the author's status, this book is helpful for understanding high-level circumstances during the pre-Cultural Revolution and early Cultural Revolution period.